Part 1 of Chapter 10 from Richard Hughes' 1997 book, Ruby & Sapphire. It covers general principles of judging quality.

Ruby & Sapphire • Judging Quality & Prices • Part 1

"That which is beautiful is never too costly, nor can anyone pay too much for that which gives pleasure to all," said Abu Inan Farés, Sultan of Morocco, on completion of a beautiful building at Fez. To emphasize his delight, he refused to look at the architect's bill, but tore it up and threw the fragments into the River Fez. Sydney H. Ball, 1935, Economic Geology

The Web version of Chapter 10 is divided into 2 sections:

Part 1 deals with quality analysis

Part 2 concludes with a Summary of important rubies & sapphires

I gotta love for Angela, I love Carlotta, too.

I no can marry both o' dem, so w'at I gona do? Thomas –1948]

Between Two Loves

MUCH of human activity concerns discretionary ability. The world is not composed of black and white, but of infinite shades of gray. Not fixed in space and time, these shades undergo continuous change. We are constantly called upon to make qualitative judgements. Such decisions are made daily – they are part of life – and our success in navigating life is closely tied to how we deal with these challenges.

For assistance, society has developed guidelines. While such rules of thumb cannot predict the future of an individual event, if they are based upon the experiences of a large sampling of people, they have utility to the individual over the long haul. But when they are based merely upon "faith," rather than empirical methods, such beliefs constitute dogma.

There is considerable evidence to suggest that many religious and cultural dogmas were at one time based on empiricism. For example, the prohibition against eating pork, widespread in Judaic and Islamic cultures, is believed to have grown out of the fact that, in desert societies, the keeping of pigs wasted precious water, and so was a selfish activity that harmed the group. But when such religions spread to wetter climes, where there was plenty of water to go around, the ban remained. Thus the problem. When empirical discovery solidifies into immobile dogma, as with the above example, the possibility of future discovery or change is ruled out, to the detriment of all.

Similarly, according to the European thought extant during the time of Columbus, the earth was flat, and it was heresy to think otherwise. This is the difference between empirical beliefs, and those based upon faith alone, i.e., those based on observation and first-hand experience, rather than assumption.

Ruby & sapphire grading • A heretic's guide

Having now committed one heresy, the discussion of religion, I shall proceed to commit another, discussion of colored stone grading.

Comparable to those who opposed the mere thought of Columbus sailing into unknown waters, today many traders and gemologists oppose even a discussion of systematic quality analysis of colored stones. Akin to the priests of the Middle Ages, who fought against translation of the Latin Bible into vernacular languages, these high priests of the gem trade apparently feel that only those properly initiated into the "Great Order of Gemmarum et Lapidum" should be allowed to dine at the quality-analysis table. Others less fortunate must be content to scramble for the crumbs of knowledge those on high deem suitable to toss their way.

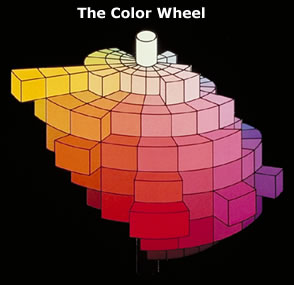

Figure 10.1 The three dimensions of color 10.1a: Three-dimensional view of a color solid. (This illustration courtesy of Minolta USA)

Figure 10.1 The three dimensions of color 10.1a: Three-dimensional view of a color solid. (This illustration courtesy of Minolta USA)

Grading systems are as old as the gem trade itself. Witness ancient India's Garuda Purana, dating back as far as 400 AD (Shastri, 1978), which classified the then-known gems into categories on the basis of their characteristics. Over the succeeding centuries, these systems have been steadily refined. Diamond grading systems made their appearance in the 20th century, but modern attempts at colored stone grading date only from the late 1970s. Problems with some of these early attempts have led many to condemn the very idea of systematic grading. In the author's opinion, this is a mistake.

Early forays into colored stone grading were primitive, and today many problems remain. This is to be found in the development of anything new. Look at the first airplanes. Clumsy and dangerous, they often killed their occupants. Today few would argue against their use, but in the beginning many did: "If humans were meant to fly, they would have been born with wings" was the typical refrain. I suppose if humans were meant to drive, we would have been born with horns and bumpers.

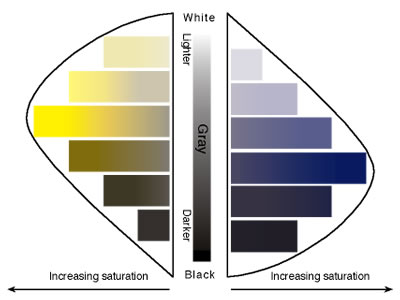

10.1b: Vertical slice through the color solid along the yellow-violet axis. Saturation increases horizontally from the center, while lightness/darkness varies along the vertical axis. Note that the highest saturation of yellow is naturally much lighter than that for violet. A slice along the green/magenta axis would show the highest saturations to have a similar lightness.

10.1b: Vertical slice through the color solid along the yellow-violet axis. Saturation increases horizontally from the center, while lightness/darkness varies along the vertical axis. Note that the highest saturation of yellow is naturally much lighter than that for violet. A slice along the green/magenta axis would show the highest saturations to have a similar lightness.

In his excellent article on the methods and benefits of colored stone grading, Nelson (1986) cataloged a large variety of trade objections. In this author's (RWH) opinion, the key criticisms are threefold:

- Like the priests who opposed translation of the Latin Bible into common languages, dealers are afraid that colored stone grading will remove their trade advantages, thus cutting the traditional gem dealer out of the picture. [1]

- In a business where the most complicated and expensive piece of equipment is often an electronic balance, traders dislike the thought of having to send their stones out for lab grading.

- Many colored stone dealers abhor the thought that their trade might become like the diamond trade, where stones with certificates are traded in an indiscriminate manner, in some cases without ever viewing the gem. As a Geneva dealer once told me: "My five-year old son can trade certificate diamonds. It requires no knowledge, no training." This is a real problem, one which gemologists must answer before they can gain trade support for colored stone grading.

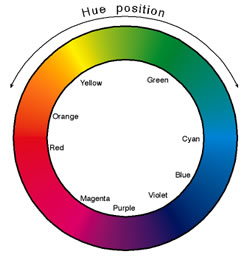

10.1c: Hue position is illustrated by the color wheel, representing a vertical slice through the color solid (the center is not shown). Mixing equal amounts of the three additive primaries (red-orange, violet, green) produces white, while equal mixtures of subtractive primaries (cyan, magenta, yellow) results in black.

10.1c: Hue position is illustrated by the color wheel, representing a vertical slice through the color solid (the center is not shown). Mixing equal amounts of the three additive primaries (red-orange, violet, green) produces white, while equal mixtures of subtractive primaries (cyan, magenta, yellow) results in black.

Unfortunately, the advantages to such a system are too often overlooked amidst the bluster and rhetoric. These benefits are the increased consumer confidence and thus, increased sales, which would follow adoption of such standards. Much time would also be saved by adoption of a standardized language for describing the appearance of colored gems.

The key to developing a successful colored stone grading system will be in creating a language useful for communicating the overall appearance of a gemstone. Once a gem is adequately described, it is then up to the marketplace to determine relative value. Attempts to assign relative values to each grade will succeed only if the considerations of the real marketplace are taken into account. To make these decisions, gemologists must work closely with traders.

An unfortunate paradox in the gem world (and one which is also present in many other fields) is that traders, who, by virtue of experience, are generally most qualified to judge quality, must be disqualified from doing so because of their bias. But traders must have input into the system for it to succeed.

The elements of quality

Quality is determined by reference to the so-called 3 c's: color, clarity and cut. While these factors are well defined for diamond, no universally-accepted system exists for colored gems. The following is based on the author's own extensive experience.

Four blue sapphires showing a variation in saturation and tone. Stone 1 possesses a light tone and low saturation. Stone 2 is close to ideal in both tone and saturation. Stone 3 has greater saturation than Stone 2 in some areas, but its overall tone is too dark and it shows too much extinction. Stone 4 is so dark in tone that its saturation is reduced. Note that inclusions are far more visible in stones of light tone than those of dark tones. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Four blue sapphires showing a variation in saturation and tone. Stone 1 possesses a light tone and low saturation. Stone 2 is close to ideal in both tone and saturation. Stone 3 has greater saturation than Stone 2 in some areas, but its overall tone is too dark and it shows too much extinction. Stone 4 is so dark in tone that its saturation is reduced. Note that inclusions are far more visible in stones of light tone than those of dark tones. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Color and appearance in colored gemstones

To the color scientist, given an opaque, matt-finished object, there are three dimensions to color:

- Hue position: The position of a color on a color wheel, i.e., red, orange, yellow, green, blue and violet. Purple is intermediate between red and violet. White and black are totally lacking in hue, and thus achromatic ('without color'). Brown is not a hue in itself, but covers a range of hues of low saturation (and often high darkness). Classic browns fall in the yellow to orange hues.

- Saturation (intensity): The richness of a color, or the degree to which a color varies from achromaticity (white and black are the two achromatic colors, each totally lacking in hue). When dealing with gems of the same basic hue position (i.e., rubies, which are all basically red in hue), differences in color quality are mainly related to differences in saturation. The strong red fluorescence of most rubies (the exception being those from the Thai/Cambodian border region) is an added boost to saturation, supercharging it past other gems that lack the effect.

- Darkness (tone or value): The degree of lightness or darkness of a color, as a function of the amount of light absorbed. White would have 0% darkness and black 100%. At their maximum saturation, some colors are naturally darker than others. For example, a rich violet is darker than even the most highly saturated yellow, while the highest saturations of red and green tend to be of similar darkness.

Figure 10.1 is a simplified illustration of the three dimensions of color.

With gems, we are not dealing with opaque, matt-finish object of uniform color. Thus it is not enough to simply describe hue position, saturation and darkness. We must also describe the color coverage, scintillation and dispersion.

Color coverage can be influenced by a variety of factors, including proportions, fluorescence and inclusions. The round Burmese red spinel at left is strongly fluorescent and the red emission adds extra power to the red body color, covering up extinction. With the fine emerald-cut Kashmir sapphire pictured at right, color coverage is improved by the presence of tiny needlelike inclusions, which scatter light across the stone, thus reducing extinction. This is what gives Kashmir sapphires their incomparable velvety color. Note that both of these gems have colors which are highly saturate, making them highly desirable. Photos: Wimon Manorotkul, John McLean

Color coverage can be influenced by a variety of factors, including proportions, fluorescence and inclusions. The round Burmese red spinel at left is strongly fluorescent and the red emission adds extra power to the red body color, covering up extinction. With the fine emerald-cut Kashmir sapphire pictured at right, color coverage is improved by the presence of tiny needlelike inclusions, which scatter light across the stone, thus reducing extinction. This is what gives Kashmir sapphires their incomparable velvety color. Note that both of these gems have colors which are highly saturate, making them highly desirable. Photos: Wimon Manorotkul, John McLean

- Color coverage: Differences in inclusions, transparency, fluorescence, cutting, zoning and pleochroism can produce vast differences in the color coverage of a gem, particularly faceted stones. A gem with a high degree of color coverage is one in which color of high saturation is seen across a large portion of its face in normal viewing positions. Tiny light-scattering inclusions, such as rutile silk, can actually improve coverage, and thus appearance, by scattering light into areas it would not otherwise strike. The end effect is to give the gem a warm, velvety appearance (Kashmir sapphires are famous for this). Red fluorescence in ruby boosts this still further.

Color zoning can also be influenced by color zoning, an unevenness of color. The oval sapphire above shows moderate color zoning. Moderate to severe color zoning does impact quality, and thus price. Color zoning is always judged in the face-up position, in an 180° arc from girdle to girdle, with the gem rotated through 360°. Color irregularities visible only through the pavilion generally do not impact value. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Proper cutting is vital to maximize color coverage. Gems cut too shallow permit only short light paths, thus reducing saturation in many areas. Such areas are termed windows. Those cut too deep allow light to exit the sides, creating dark or black areas termed extinction. Areas which allow total internal reflection will display the most highly saturated colors. These areas are termed brilliance. Color zoning can also reduce color coverage. Ideally, no zoning or unevenness should be present. Pleochroism is sometimes noticeable in ruby and sapphire. It typically appears as two areas of lower intensity and/or slightly different hue on opposite sides of the stone. This is most notable when the table facet lies parallel to the c axis. In summary, a top-quality gem would display the hue of maximum saturation across a large percentage of its surface in all viewing positions. The closer a gem approaches this ideal, the better its color coverage.

- Scintillation ('sparkle'): This is an important factor in faceted stones. A gem cut with a smooth, cone-shaped pavilion could display full brilliance, but would lack scintillation. Thus the use of small facets to create sparkle as the gem, light or eye is moved. In general, large gems require more facets; small gems should have less, for tiny reflections cannot be individually distinguished by the eye (resulting in a blurred appearance).

- Dispersion ('fire'): This involves splitting of white light into its spectral colors as it passes through two non-parallel surfaces (such as a prism). The dispersion of corundum is so low (0.028) and the masking effect of the rich body color so high, that it is generally not a factor in ruby and sapphire evaluation.

Clarity

Clarity is judged by reference to inclusions. Magnification can be used to locate inclusions, but with the exception of inclusions which might affect durability, only those visible to the naked eye should influence the final grade.

|

Background checks When you are examining a colored gemstone, act like a cop – always do a background check. The color of the background against which a gem is examined can have a major effect on color. Which is why wily Burmese and Thai miners traditionally offer up rubies to buyers on brass plates or yellow table tops. The yellow background color counters the bluish tint commonly present in ruby, making the gems appear more red. Yellow cellophane-lined stone papers or brass tweezers serve the same purpose. Don't be a sucker. For judging color, a plain white background is best.

|

There are two key factors in judging clarity. These are:

Visibility

- Size: Smaller inclusions are less distracting, and thus, better.

- Number: Generally, the fewer the inclusions, the better.

- Contrast: Inclusions of low contrast (compared with the gem's RI and color) are less visible, and thus, better.

- Location: Inclusions in inconspicuous locations (i.e., near the girdle rather than directly under the table facet) affect value less. Similarly, a feather perpendicular to the table is less likely to be seen than one lying parallel to the table.

Affect on durability

- Type: Unhealed cracks may not only be unsightly, but also lower a gem's resistance to damage. They are thus less desirable than a well-healed fracture. As already mentioned, tiny quantities of exsolved silk may actually improve a gem's appearance, and thus, value.

- Location: A crack near the culet or corner would obviously increase the chances of breakage more than one well into the gem. Similarly, an open fracture on the crown is more likely to chip than one on the pavilion.

Among the problems of existing colored stone grading systems is that the model chosen is based on diamond. While diamond does share a number of quality factors with ruby and sapphire, others are partly or wholly inappropriate. For example, beauty in diamond is largely a function of the material's brilliance and dispersion ('fire'). Any inclusions which alter the path of light could be detrimental to a diamond's appearance. [2] Perfect clarity is thus the ideal. As described above, perfect clarity is not necessarily the ideal for ruby and sapphire. While fractures and most other inclusions do have a detrimental effect on appearance and durability, small quantities of finely dispersed inclusions (such as exsolved rutile silk) can actually improve a richly colored gem's appearance. The watchword here is small; too much silk decreases transparency by scattering, reducing color saturation, and thus producing a more grayish color. [3]

Cut ('make')

The function of the cut is to display the gem's inherent beauty to the greatest extent possible. Since this involves aesthetic preferences upon which there is little agreement, such as shape and faceting styles, this is the most subjective of all aspect of quality analysis.

Evaluation of cut involves five major factors:

Shape

This describes the girdle outline of the gem, i.e. round, oval, cushion, emerald, etc. While preferences in this area are largely a personal choice, due to market demand and cutting yields, certain shapes fetch a premium. For ruby and sapphire, ovals and cushions are the norm. Rounds and emerald shapes are more rare, and so receive a premium from about 10–20% above the oval price. Pears and marquises are less desirable, and so trade about 10–20% less than ovals of the same quality. The shape of a cut gem almost always relates to the original shape of the rough. Thus the prevalence of certain shapes, such as ovals, which allow greatest weight retention.

Cutting style

The cutting style (facet pattern) is also a rather subjective choice. Again, because of market demand, manufacturing speed and cutting yields, certain styles of cut may fetch premiums. The mixed cut (brilliant crown/step pavilion) is the market standard for ruby and sapphire.

If a gem is cut too shallow, light will pass straight through, rather than returning to the eye as brilliance. This is termed a "window" (right). In well-cut gems, most light returns as brilliance (left). Brilliant areas are those showing bright reflections. Extinction is used to describe dark areas where little or no light returns to the eye. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

If a gem is cut too shallow, light will pass straight through, rather than returning to the eye as brilliance. This is termed a "window" (right). In well-cut gems, most light returns as brilliance (left). Brilliant areas are those showing bright reflections. Extinction is used to describe dark areas where little or no light returns to the eye. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Proportions

The faceted cut for ruby and sapphire is to create maximum brilliance and scintillation in the most symmetrically pleasing manner. Faceted gems feature two parts, crown and pavilion. The crown's job is to catch light and create scintillation (and dispersion, in the case of diamond), while the pavilion is responsible for both brilliance and scintillation. Generally, when the crown height is too low, the gem lacks sparkle. Shallow pavilions create windows, while overly deep pavilions create extinction. Again, proportions often are dictated by the shape of the rough material. Thus to conserve weight, Sri Lankan material (which typically occurs in spindle-shaped hexagonal bipyramids) is generally cut with overly deep pavilions, while Thai/Cambodian rubies (which occur as thin, tabular crystals) are often far too shallow.

- Depth percentage: In attempting to quantify a gem's proportions, reference is often made to depth percentage. This is calculated by taking the depth and dividing it by the girdle diameter (or average diameter, in the case of non-round stones). The acceptable range is generally 60–80%.

- Length-to-width ratio: Another measurement that is used for non-round stones is the length-to-width ratio. Overly narrow or wide gems of certain shapes are generally not desirable.

Symmetry

Like any finely-crafted product, well-cut gems display an obvious attention to detail. A failure to take proper care evidences itself in a number of ways, including the following:

- Asymmetrical girdle outline

- Off-center culet or keel line

- Off-center table facet

- Overly narrow/wide shoulders (pears and heart shapes)

- Overly narrow/deep cleft (heart shapes)

- Overly thick/thin girdle

- Poor crown/pavilion alignment

- Table not parallel to girdle plane

- Wavy girdle

Finish

Lack of care in the finish department is less of a problem than the major symmetry defects above, because it can usually be corrected by simple repolishing. Finish defects include:

- Facets do not meet at a point

- Misshapen facets

- Rounded facet junctions

- Poor polish (obvious polishing marks or scratches)

While these guidelines may be useful, one must not become a slave to them. In essence, the cut should display the gem's beauty to best advantage, while not presenting mounting or durability problems. If the gem is beautifully cut, things such as depth percentage or length-to-width ratio matter not one bit. What works, works.

Influence of lighting on color

With any colored gemstone, the color seen depends on the light source used to illuminate it. Over time, gem dealers have come to rely on skylight for their gem buying. Its major advantage is its strength, which ruthlessly reveals flaws. The quantity of light coming through even a modest-sized window is far greater than even the strongest, color-balanced fluorescent tube (or tubes). Another factor appears to be the large radiating area, when compared with the most artificial lights.

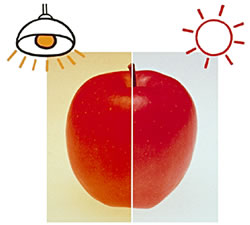

Figure 10.3 Lighting can have a dramatic effect on the appearance of any colored gem. Incandescent lighting (left) is rich in red, orange and yellow wavelengths and thus pushes an object's color in that direction. In contrast, skylight (right) is more balanced, pushing the color in the opposite direction. (Illustration: Minolta)

Latitude may also affect a stone's color, simply because skylight is stronger in the tropics. As a result, gems bought in the tropics will appear slightly darker when taken to more temperate climes. It is a slight, but nevertheless, noticeable difference. Surprisingly, north skylight (or south skylight in the southern hemisphere) is actually stronger on cloudy days.

Another factor is the Purkinje shift. [4] In bright light, the eye is more sensitive to red; conversely, in dim light the eye is more sensitive to blue-violet light. Thus the color of blue sapphires would be slightly enhanced in dim lighting.

The question of north skylight

North daylight (skylight, as opposed to direct sunlight) has become the standard, because it produces the least glare, but blind adherence to such gemological dogma is just as bad as blind adherence to religious dogma. If you live north of the Tropic of Cancer (Europe, North America, Japan, China, etc.), north skylight will provide the least glare year round, because the sun always passes through the southern portion of the sky. This is especially true the farther north one goes. The opposite holds true for those who reside south of the Tropic of Capricorn (in the southern hemisphere), where the least glare is found using south skylight.

What about those who live in the tropics? If they are north of the equator, north skylight is best, except May-July, when south skylight is preferred. For the tropics south of the equator, south skylight is best, except from Nov.-Jan., when north skylight is preferred. And if you live right on the equator, use north skylight from Oct.-Feb., and south skylight from April-August. During March and Sept., either north or south skylight can be used.

Time of day

Even skylight changes throughout the day. Generally speaking, rubies (and other red stones) look best during the midday hours. Sapphires, in contrast, look best in the early morning or late afternoon. If you are buying, this means that rubies should be purchased early or late in the day, while sapphires are best bought near midday, thereby preventing a surprise when the stone is examined under another lighting condition.

The above is in contrast to what is often reported (Newman, 1994, p. 38). While direct sunlight is far more red at sunrise and sunset, the skylight is actually more blue. Since we use skylight, not direct sunlight, to illuminate gems, blue color will be enhanced early and late in the day. Similarly, the skylight at noon is less blue, thus enhancing the color of rubies in the middle of the day.

Weather and pollution

How might clouds or pollution affect color? Heavily-polluted or cloudy skies will result in more grayish (less blue) skylight, thus improving the appearance of rubies (as opposed to sapphires).

The Buddhist temple at Swayambunath, Nepal, silhouetted against a deep blue sky. It is obvious that such skylight would enhance the appearance of blue stones.

Fog in Sri Lanka's central highlands. The high moisture content gives the light a grayish cast.

Sunset on Sri Lanka's western coast. While such sunlight could easily enhance the color of red and yellow stones, it should be noted that direct sunlight is rarely used for examining gems. (Photos © R.W. Hughes)

Artificial lighting

Some type of artificial light is obviously the answer to neutralize the above factors. Many dealers today do their buying under special daylight lamps designed to simulate true north daylight, with a color temperature of approximately 5000–6100°Kelvin. Generally speaking, while their color balance is similar to north daylight, the fluorescent tubes used suffer from low light output. A 20-watt fluorescent daylight tube at a distance of 30 cm produces about 1000 lux of illumination, while a north-facing window in Bangkok averages 6000 lux.

The answer appears to be short-arc xenon lamps. While rather expensive (compared to fluorescent lamps), they have a continuous output (like daylight), 6000°K color temperature, and produce illumination levels comparable to north daylight.

For an excellent summary of the entire lighting question, see Sersen & Hopkins (1989) and Sersen (1990), from which the above is derived.

Figure 10.5 When grading gems, viewing geometry, background and controlled lighting are crucial. The woman above is sorting sapphire rough from Australia. (Photo: Great Northern)

Figure 10.5 When grading gems, viewing geometry, background and controlled lighting are crucial. The woman above is sorting sapphire rough from Australia. (Photo: Great Northern)

Viewing geometry & background

Gems are designed to be mounted in jewelry and viewed from predetermined angles. This is generally face-up, with the gem viewed in a 180° arc from girdle to girdle. Thus it is only logical that all quality determinations be made with the naked eye under the same viewing geometry. It is important that the gem be rotated through 360° in the girdle plane, so that its appearance is seen from all angles, just as it would be when mounted in jewelry.

To ensure reproducibility and repeatability, a standardized light source against a standardized, neutral background (white is best) at a standardized distance should be used. The practice in diamond grading of judging body color through the pavilion facets is madness, and has no place in colored stone grading. [5]

Summary of quality

The appearance of a colored gem is a combination of many separate factors, each of which is related to, and affect, the others. It is precisely the complexity of these intertwined relationships that has bedeviled previous attempts to quantify quality. And yet, every time a dealer buys a gem, a quick mental analysis is made, usually within seconds. In grading any gem, one must be cognizant of, but not become lost in, the details. When all the minutiae has been pored over ad infinitum, ad nauseam, take a step back and simply look at the gem. In the age of high-powered microscopes this may constitute a radical concept, but one which is necessary.

Fine precious stones are comparable to great works of art. Like a painting, to appreciate it, one must view the whole, not just the parts.

Pricing factors

Prices of Genuine Jewels

The prices of jewels are not stable. There is no law governing their prices, and there is no reason why these prices should not fluctuate with time and place. Each country, each nation carries its own temper. Furthermore, at one time nobles begin to sell them off and at others, to stock them. Stones are plentiful at one time and scarce at another. God grants honour to some and disgrace to others.

al-Biruni, 11th century AD

Kitab al-Jamahir fi Ma'rifat al-Jawahir

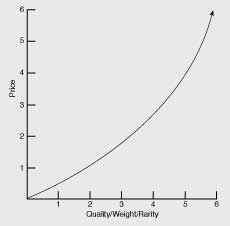

One of the great mysteries for novices is the relationship between price and quality. In a perfect world, price would directly relate to quality/weight/rarity. Unfortunately, Planet Gem is far from symmetrical. Market factors can have as much, or even greater, impact on prices as does quality. Prices are influenced by the following factors:

- Quality: Better qualities are more rare than lower qualities of the same size (see previous section).

- Weight: Bigger stones are more rare, and so more expensive per carat than the same quality of a smaller size.

- Market factors: This is the great intangible. Market factors can dramatically affect price.

Weight

Generally, as a gem's weight increases, so does the per carat price. This is shown in Figure 1.6.

Figure 10.6 Graph representing the relationship between price and quality/weight/rarity. Note that this is not a linear relationship. Price increases more quickly as quality/weight/rarity increases.

Such a relationship has long been known, and was first quantified by Villafane in 1572, for diamonds. Today it is most commonly referred to as the 'Indian Law' or 'Tavernier's Law', and works as follows (Lenzen, 1970):

| Weight of gem | = 5 ct (Wt) |

| Cost of a 1-ct gem of equal quality | = $1000 (C) |

| Calculation: 5 x 5 x 1000 | = $25,000 total stone price |

The following shows how the price of a gem might increase with this formula applied using a $1000/ct base price.

| Weight | Total stone price |

| 1 ct | $1000 |

| 2 ct | $4000 |

| 3 ct | $9000 |

| 4 ct | $16,000 |

| 5 ct | $25,000 |

| 10 ct | $100,000 |

Unfortunately, things were not so simple, even for diamonds in the time of Tavernier. The law could not accurately predict the price of diamond below 1 ct, and there were also problems with exceptionally large stones. But it does give a general idea of how prices increase with size.

|

Carat psychology In the case of many gems, including ruby and sapphire, psychological (but all too real) price jumps occur at certain weights. For example, a 0.99-ct ruby might be worth significantly less than one which weighs 1.05 ct. The 1.05 ruby would be worth more than one which weighed exactly 1.00 ct, as repolishing a 1.00-ct stone (or weighing it on someone else's scale) might send it below the important 1-ct barrier. Similar psychological weight hurdles are found at the 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100-ct levels. |

Market factors

Just a few of the market factors that influence price include:

- Market supply vs. demand: Items which are plentiful and/or in low demand will be cheaper than those which are rare and/or in high demand.

- Financial situation of the seller: Sellers who need money will obviously be more flexible on price. Similarly, those who are not in need are less willing to reduce their price.

- Seller's business overhead: Prices can vary dramatically depending on the seller's overhead. A cup of coffee purchased by a street vendor may cost only a few cents; the same cup of coffee at a 5-star hotel in the same city may cost 10–20 times more, due to the hotel's higher overhead.

- Buyer's financial situation: Buyers whose businesses are prospering are often willing to pay higher prices.

- Buyer's sales prospect: Buyers who have a customer waiting for an item are often willing to pay higher prices.

- Buyer/seller personal relationship: No one likes to do business with unhappy or abusive people. When the buyer and seller enjoy each other's company, they often make special provisions for one another.

- Personal situation surrounding the sale: The author has seen buyers pay above-average prices for goods for a variety of reasons. These have ranged from trying to impress one's girlfriend, [6] to buying something simply to prevent a competitor from purchasing the same goods.

For a generalized list of ruby and sapphire prices, see "Ruby & sapphire prices", p. 491.

Notes

- The idea of the traditional dealer is one sorely in need of definition, considering that the tradition of many so-called "traditional" gem dealers dates back less than 30 years. [ return to text ]

- Unfortunately, the current diamond-grading system, largely based on the GIA model, has applied this idea in an overly zealous manner. Thus even a single microscopic inclusion, which in no way affect a diamond's appearance, removes it from the top clarity category. Many of the upper clarity grades have absolutely no visible difference in naked-eye appearance (see Hughes, 1987b, 1991). [ return to text ]

- Stones which look good from a distance, but upon closer examination exhibit clarity problems are termed bluff stones. [ return to text ]

- Johannes von Purkinje, a Czech physiologist, observed while walking in the fields in 1825 that blue flowers appeared brighter at dawn than at midday (Varley, 1983). [ return to text ]

- Nor in diamond grading, but that is another subject. [ return to text ]

- Apparently the lady was suitably impressed, for she is now his wife. [ return to text ]