A short autobiography of Richard Hughes' life in gems and gemology. From the introduction to his 2017 book, Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide.

So we shall let the reader answer this question for himself: who is the happier man, he who has braved the storm of life and lived or he who has stayed securely on shore and merely existed Hunter S. Thompson

Richard W. Hughes • Something of Myself

It is said that everything has a beginning, middle, and end. And so it is with Ruby & Sapphire: The Gemologist’s Guide. In telling the tale, perhaps it is best to begin with my own story. Like holy books, I shall start at the beginning...

University can wait

Seeds of the present volume were sown at age 17, with a classmate’s invitation to visit Europe upon graduation from high school. “Let’s go! University can wait,” Seth teased. “What better way to learn than to drink directly from the Fountain of Life? Just imagine, we’ll run with Hemingway’s bulls, explore life’s meaning with Sartre on the banks of the Seine, discover love to a symphony of Crete sunsets. And have a damned good time, to boot. Whaddya say?”

Honestly, I was not familiar with Hemingway or his bulls, had no clue who Sartre was or where the Seine ran and Crete sounded something like a ghost town in Colorado. But the idea of going somewhere exotic and foreign appealed to me. As I lay in bed that night, I decided this is what I would do after graduation. Having drifted aimlessly through school, I finally had a purpose, a direction in life. And shortly announced the same to my parents. I was captive—swallowing hook, line, sinker, and angler’s elbow. Two weeks after graduation, Seth and I were flying Icelandic Airways from Chicago to Luxembourg. The world lay at our feet. We were on the cusp of the first of life’s great adventures.

The author's plane ticket to Europe from 1976, and his return ticket home from Thailand in 1977, after nearly a year spent traveling around the world.

The author's plane ticket to Europe from 1976, and his return ticket home from Thailand in 1977, after nearly a year spent traveling around the world.

Go East, young man!

Asia was not initially in the cards. Seth and I had planned to winter in Israel, and return to Europe in the spring. But, in one of those glorious accidents that changes a life, I met someone in Copenhagen who had just made the overland journey from Asia. As Colin described the wonders of the East, I listened with rapt attention. Istanbul, Delhi, Rangoon, Bangkok—the names rolled off his tongue like a Kipling verse. And then he spoke the magic word—Nepal.

Now, one must understand. I had grown up in Boulder, Colorado, mountaineering Mecca of America. Reared on National Geographic documentaries showing climbers with their army of porters marching towards Everest, for me visiting the Himalayas represented almost a religious pilgrimage. They were the cherry on the sundae, the holy grail, the positively Penny Pingleton punishment big P pink flamingo on the suburban lawn. Dangling Nepal out there was like asking a 15-year old if he wouldn’t mind keeping your stripper cousin company while you studied for finals. Then Colin casually mentioned that transport between Istanbul and Nepal would probably run, say... $35. This, for a journey of some 5000 km. That sealed it. The die was cast, the hook was set, it was written. I had heard the Sirens’ song and would answer the call.

Indeed, Colin was right. The Eastern lands proved every bit as splendid as described. But in terms of travel expenses, he had erred. It cost me only $25 to travel between Istanbul and Nepal.

Celebrating life in Zanzibar, East Africa.

Celebrating life in Zanzibar, East Africa.

Out of Africa

Before I jumped into Asia, Seth and I made a small detour to Morocco, for a taste of the Third World. While waiting for the ferry from Algeciras to Ceuta, we made the acquaintance of Michael, an African American from Detroit, who was to become our traveling companion during the next several weeks.

Our days in Morocco were... enlightening. From the moment we crossed the border at Ceuta, we were hassled, hustled, harassed, harangued and otherwise swindled. Things came to a head in Fez, where we gathered in a decrepit hostelry, plotting escape from the madness.“Ya know, Mike,” Seth and I opined,“You could pass for a Moroccan. Particularly if you wear one of those Moroccan djellabas (robes) you bought yesterday. Then we can go everywhere without being hassled—the street hustlers will think you’re with us.” Begrudgingly, he agreed the plan was a good one and thus, with Mike suitably attired, we boldly hit the streets. After strolling about a block, with passersby staring and nervously twittering, a voice suddenly cried out from a streetside café: “Hey black man. You’re wearing a woman’s djellaba!”

Something of Myself

Ten days after our arrival, weightier in wisdom, but far lighter in coin, Morocco spit us onto the deck of a Tangier ferry. We landed with an impotent bleat. Our last act in that fair land had been the purchase of a Herald Tribune, which proved to date from even before our arrival.

Istanbul is Constantinople

Ship me somewheres east of Suez, where the best is like the worst,

Where there aren’t no Ten Commandments an’ a man can raise a thirst... Rudyard Kipling, Mandalay

Seth and I parted company in Greece; he headed for Israel and his own personal pilgrimage, I for Asia and mine. My first stop was Istanbul.

Mt. Ararat from the Turkey-Iran border at Tabriz—1976

Mt. Ararat from the Turkey-Iran border at Tabriz—1976

The Straits of Bosporus, less than one km wide, mark the physical separation between Europe and Asia. But the chasm of time between these two great continents can be measured in millennia. In rural Asia, I was quickly introduced to life as it was centuries before. A big part of that is precious stones, which remain an integral item of trade in much of the East. From Iran’s turquoise, through Afghanistan’s lapis lazuli, to the rubies, sapphires, and jade of Myanmar and Thailand, jewels and jewelry are a constant fixture.

Peter on the Afghan-Pakistan border—1976

Peter on the Afghan-Pakistan border—1976

India at last

India is best summed up in the comment of one of my fellow travelers, who declared: “It seems to survive in spite of itself.” While you either love it or hate it, I found myself doing a bit of both. More than in any other land I visited, I felt transported back to another age.

Since the 15th century, the destination of most overland travelers from Europe was the same—India. I will never forget my first experience. One of the delights of overland travel is that of crossing land borders. Sudden changes in mood and culture always bring surprises. And the Pakistan-India border was a ten. While the Persians had set up an entire museum at the Afghan border to deter smugglers, demonstrating the various ways they had been caught, India took a more subliminal approach. Travelers were set in line, and handlers brought a psychic out. She slowly approached each traveler and, after a wave of the hand over the forehead, said sternly:“Where is your contraband?” While I never heard of anyone breaking down into a slobbering heap, it was said she was “very good at detecting smugglers.”

My friend, Peter, and I took the bus into Amritsar. Seth and I had first met Peter in Berlin; later I stumbled upon him on a Khyber Pass-bound bus in Kabul. Over the next several months, Peter and I would experience the subcontinent together.

At the Amritsar bus station, inside the station, in line, was a cow, seemingly waiting for a ticket on the last bus out. Welcome to India. Our first night there was spent sleeping inside the Golden Temple, scene of the Sikh siege in 1984.

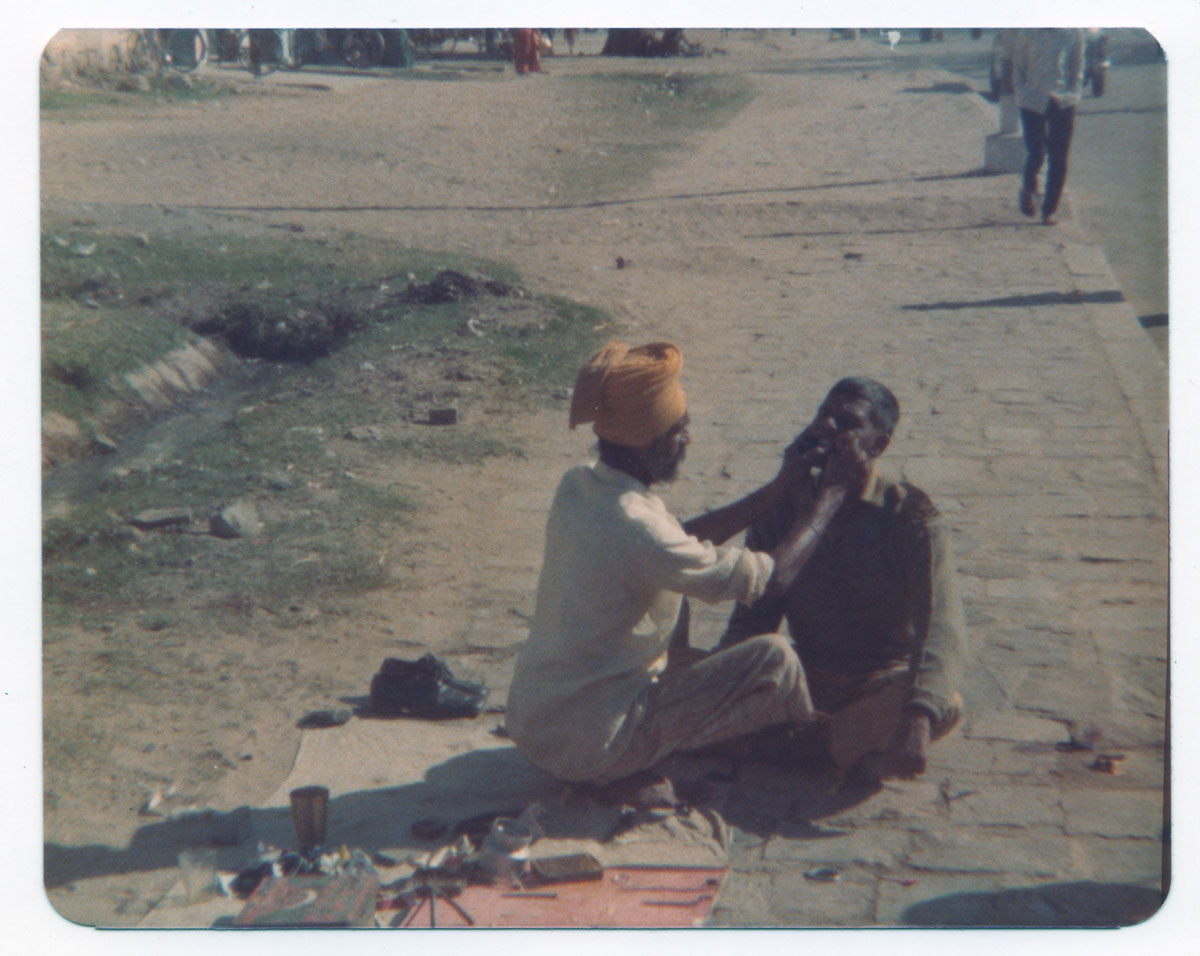

A Jaipur dentist—1976. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

A Jaipur dentist—1976. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Jewels from the mine

My career in gems got off to an ignominious start. Having been offered various and sundry “jewels and priceless relics” from all points east of Istanbul, Peter and I decided to take the plunge in Jaipur. Throwing caution to the wind, we would purchase a small parcel of Indian star rubies for resale. Our search began in a wee little jewelry shop near Jaipur’s Hawa Mahal (Hall of Winds).

Clever chaps that we were, Peter and I concluded we needed a good ruse. Deep in the core of our being, we just knew that the vulpine Oriental venders would hold back the finest goods. Thus we demanded the seller “bring out the good stuff ” after each parcel was displayed. Peter, playing the best Abbott to my Costello, would pass a packet across the table for my look-see. Upon poring over a single $1/ct ruby for ten minutes, holding both stone and loupe at arm’s length, and checking the star from all directions, I then pronounced judgment: “My good man, this will just not do! We are big dealers, with no time to waste! Show us the good stuff!”

Not even a single paisa descended from heaven. Instead, following several parcels and several rejections, the seller looked us straight in the eye and, in the vernacular, told us we were full of that which emanates from the rear of a Hindu holy animal. He then proceeded to scold us, explaining that, from the moment we stepped into his shop, it was obvious we were simple tourists, not dealers. Such was apparent merely by the way we handled the loupe and stone papers, not to mention the fact that I had failed to notice the star on one stone because it was upside down. We beat a hasty retreat and, regrouping outside, decided our hiking boots must have given us away.

Kathmandu

Peter and I arrived at Raxaul, on the Nepalese border, at midday. Too late to catch the bus to Kathmandu, but with the Himalayan foothills glistening in the distance, we would not be deterred. We immediately set off for the frontier. Like so many Asian land borders, the station on one side was a distance from that on the other. Leaving India was, well, Indian—all hassle and uncertainty. Crossing the small stream that delineated the border, one immediately entered another world.“Would the customs agent like to see our bags?” Only if we had a mind to carry them from the horse buggy into the shed. “And would he mind chopping our walking papers anyway?” Of course, with a smile. Namasté. Welcome to Nepal.

India-Nepal Border at Raxaul—December 1976

India-Nepal Border at Raxaul—December 1976

On the Nepalese side, the Himalayas beckoned. We quickly found a truck driven by a Sikh, heading for Kathmandu that very night.“Were we interested?” Would a bear shit in the Vatican? As December’s dusk slowly enveloped the surrounding Terai, we set off. The sun’s last rays blazed in our wake as we entered the foothills. Midnight came and went and we still headed up, twisting and turning into a Himalayan wonderland, with only our imaginations and the truck’s weak head lamps illuminating our path.

Many Indian trucks have a storage space above the cab and so I climbed up to stretch out just past midnight. It was there that I completed the journey, amidst trees, stars, and the hopes of a young boy living his dream. As the sun rose, we descended into the Kathmandu valley. Paradise found. It was pure magic. Even today, words seem utterly inadequate. My stay in the Kingdom lasted two months and included a month-long trek to the Himalaya’s inner sanctum at Mt. Everest’s base camp. I was hooked, and have since revisited Nepal again and again. If there is heaven on earth, it is in Nepal.

Richard Hughes, Tangboche Monastery, Khumbu, Nepal—January 1977. At this point, I had not bathed in close to one month, but it was not a problem, as I had reached hygenic equilibrium with my environment. i could pick up hot coals off a fire with my bare hands and feel no pain. I was living the dream.

Richard Hughes, Tangboche Monastery, Khumbu, Nepal—January 1977. At this point, I had not bathed in close to one month, but it was not a problem, as I had reached hygenic equilibrium with my environment. i could pick up hot coals off a fire with my bare hands and feel no pain. I was living the dream.

Oh, Calcutta

From Nepal, I beat a swift path to Calcutta, original capital of the British Raj. Anyone who has traveled to India has heard the Calcutta horror stories—the beggars, the cripples, the grinding poverty... Expecting the worst, I arrived at Howrah station at dawn, just slightly tattered, considering I spent the trip in a luggage rack on an Indian train. Instead of despair, I found a vibrant city, one which continues to be my favorite metropolis on the subcontinent.

Burmese Days

Depending on how one worked it, Myanmar (Burma) was either the most, or least, expensive country in Asia. Officially, $1 bought six kyat; unofficially, it was closer to thirty. The game was thus: tourists could legally import one carton of cigarettes and one liter of whisky. Obtained at Kolkata’s (Calcutta) Dum Dum airport (allegedly named in honor of the fact that it was the first site where dum-dum bullets were used), these would be sold for several times their value in Rangoon. With the exchange of $10 at the legal rate, to satisfy Burmese officialdom, the proceeds were enough to live on for the full week, and then some.

Superficially, Ne Win’s Burmese Road to Socialism appeared like the disordered in charge of the disenfranchised, with all in disarray. But evidently somebody was keeping track—six copies were required for every visa application.

Myanmar represented a topsy-turvy, never-never land where up was down, down was sideways and time moved only slightly above the stall speed of a bicycle. Central government policies had so decimated the manufacturing and agricultural sectors that even basic necessities had to be purchased on the black market. And so ubiquitous was this black market that locals called it the brown market. One of Myanmar’s most important products was gems. I recall trading an old and dirty towel for an orange spinel in Mandalay and, to this day, continue to be bewildered that anyone would want that rag. As the saying goes: “In the Land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.”

Yangon’s Sule Pagoda—February 1977

Yangon’s Sule Pagoda—February 1977

Bangkok Nights

If Kublai Khan’s pleasure dome could be reincarnated in the 20th century, it would rest in Bangkok. Like parched survivors emerging from the Sahara, overland travelers deplaned in Bangkok to a world long-since forgotten. For the first time since Istanbul, one found unheard of luxuries—air conditioning, ice cream, cold beer, girls in miniskirts—it was more than a grown man could take. As a mere teenager, I made sure to get a full adolescent’s share. Little did I know it was destined to become my home.

Thailand was, is, and probably always will be, one of the most glorious places on the planet. A place of enjoyment, a place of warmth, a place of good cheer, a place of jai dee (good heart) and sanuk dee (good fun). Indeed, it is the Land of Smiles. And a smile is always better than a frown.

Getting down to business

Somewhere it is written that every Bangkok resident should aspire to open either a travel agency or jewelry store. Since I was living in Bangkok, and since I cared nothing for the vagaries of ticketing others to paradise, I chose gems. My entrée took the form of a gemology class at the newly-minted Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences (AIGS). One thing led to another. Next I knew, I was working at and, soon, managing the Institute. Once more, university could wait.

It was exciting, particularly in the beginning. The school’s owners ran one of Bangkok’s largest wholesale gem houses. Each morning we would troop in early to check the goods purchased the previous day, with loupe and tweezers our only tools. Buyers came from around the world, particularly Japan—we quickly learned the tastes of each. Best of all, we would play the precious-stone version of The Price is Right, guessing the cost of each lot before checking what had really been paid. It was an invaluable experience.

On the border

Weekends were often spent at the Burmese border, particularly Mae Sot. An overnight bus on Saturday night put me in Mae Sot Sunday morning, giving daylight hours for stone purchases. Then it was back on the bus for Bangkok, a quick shower and work Monday morning. When not in Bangkok or Mae Sot, I was off visiting the Cambodian border, Mae Sai, Bo Ploi, Phrae, Chanthaburi, India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar. Seven days a week, I lived, stroked, inhaled precious stones. It was, and is, and has remained my passion.

By hook and by book

As all close to me can testify, I suffer a terminal love of books. Thus the first task I undertook after being hired at AIGS was the creation of a library. But it was a colleague, Bill Spengler, who kindled my interest in antiquarian books. Bill had grown up in Kabul and Peshawar and was constantly traveling hither and yon. When he returned from one Calcutta sojourn with an Indian edition of Tavernier’s Travels, I was fascinated. Soon I was doing the same, stocking AIGS and my own library with the obscure, the interesting, the fascinating... along with plotting my own literary career.

Push comes to shove

Inspiration to write came via two contrary channels. The push was a pair of books with which I had fallen in love: Kunz & Stevenson’s Book of the Pearl and John Sinkankas’ Emeralds and other Beryls. The word magnificent does not do these works justice. Their pages put the thought in my mind to do a similar volume on ruby and sapphire. Shove occurred during a particularly distasteful corporate “motivational” retreat. I suppose it worked. Then and there I made the decision to begin doing things for my own welfare, rather than being a mere cog in someone else’s machine. In retrospect, this was one of the most important lessons of my life.

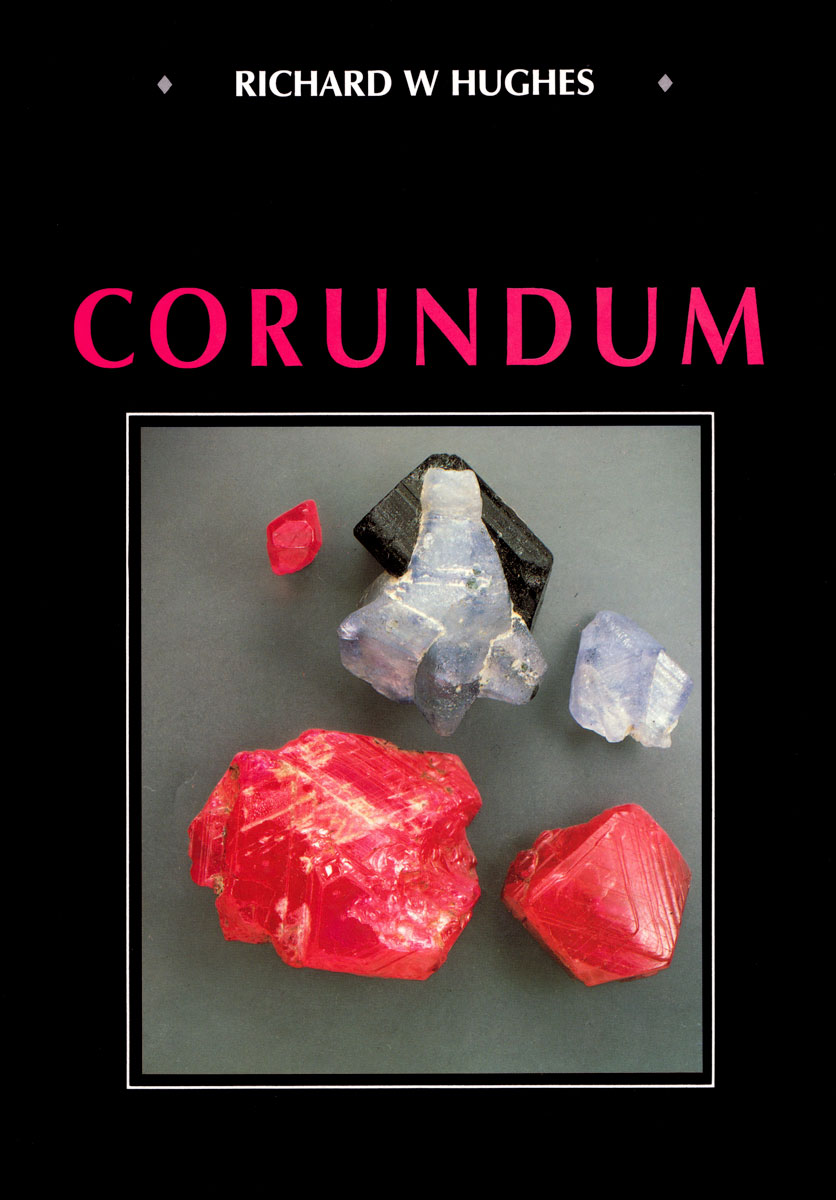

The author’s first book, "Corundum," from 1990

The author’s first book, "Corundum," from 1990

Love potion number 3.32

Life was not all work and no play. I did find time for other activities. Among my varied duties was working in the closet-like confines of the AIGS lab. It was there, amidst the ever-present odor of diiodomethane (methylene iodide), that love came to town. My colleague, Wimon, and I were eventually married, and now have a beautiful daughter, Erin Billie. Among other things, we share a passion for precious stones and sashimi. And whenever we smell methylene iodide, we still get all worked up...

Wimon and Billie at our home in Bangkok, circa 1991. Note the rotary dial phone and the humongous stack of phone books. Making any sort of phone call in Bangkok at that time was a masochistic exercise. Just getting a phone line cost US$1000 or more [official price, very cheap; you want it now instead of years later? $1000].

Wimon and Billie at our home in Bangkok, circa 1991. Note the rotary dial phone and the humongous stack of phone books. Making any sort of phone call in Bangkok at that time was a masochistic exercise. Just getting a phone line cost US$1000 or more [official price, very cheap; you want it now instead of years later? $1000].

The Gemological Enquirer

Mark Twain and I are in very much the same position. We have to put things in such a way as to make people who would otherwise hang us, believe that we are joking. George Bernard Shaw

While the first edition of Ruby & Sapphire [Corundum] was inthe hands of the publisher, I began work on a periodical, entitled Gemological Digest. A better appellation would have been the Gemological Enquirer, for, compared to the staid cud typically doled out by test-tube publishers, it must have seemed like a supermarket tabloid. Verily.

In our quest for irreverence, more than a few sacred cows had their hides peeled off. I can say with some satisfaction that certain industry figures are still haunted by thoughts of what was printed.

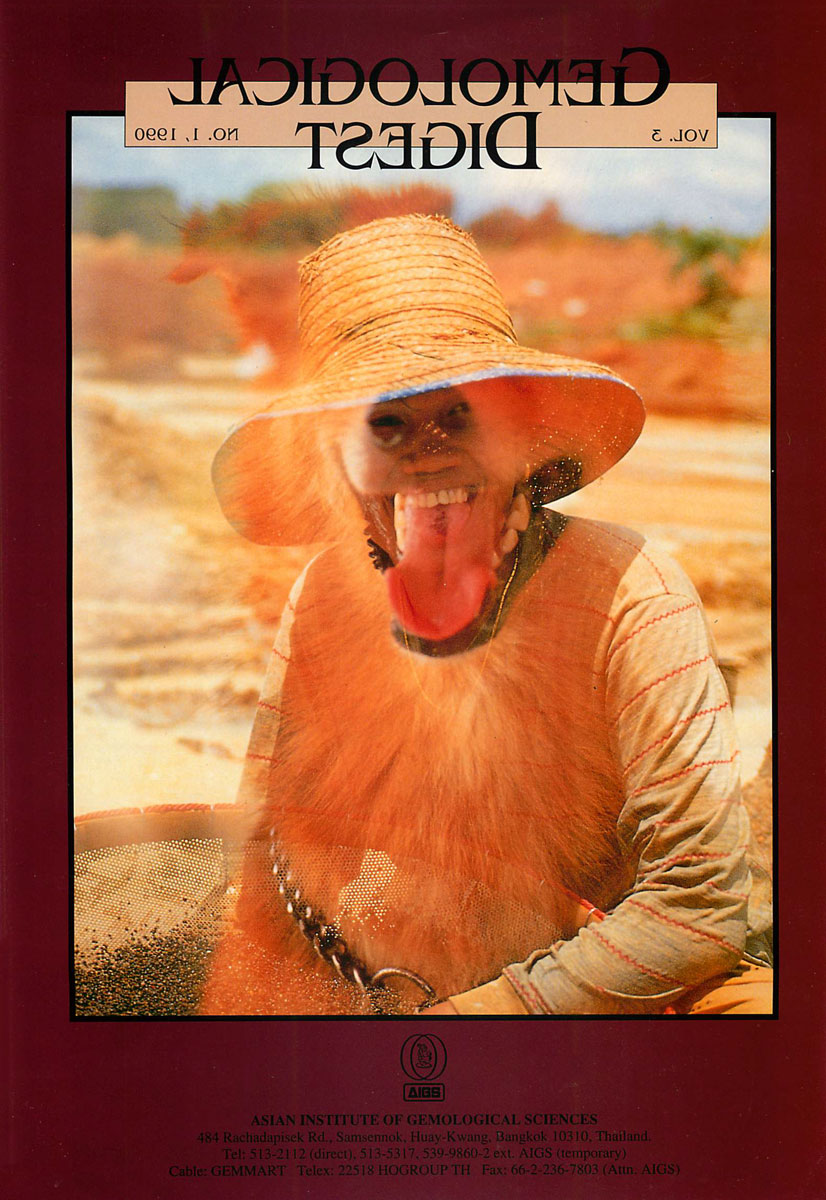

Case in point was a photo we placed on the back cover of one issue. A student had taken a picture of his dog in France and then came to Thailand and snapped a photo of a ruby miner with rubies on her tongue. But the camera was broken and an unbelievable accidental double exposure was the result. All hell broke loose upon publication. We even heard from the dog’s agent, who complained that we had captured his “bad side.”

I will always remember my employer’s skittish disposition whenever I submitted a new issue for vetting. After pausing to read it, Henry would cluck and titter like a nervous hen:

Let’s see, this time you’ve insulted Ne Win, De Beers, the Thai military, GIA, CIBJO, organized religion—the old, the young and the restless— atheists, beggars, blind hookers and the entire cast of Rambo. You missed the Pope. Feelin’ okay?

Warming to the task, Henry would then consult his shopworn copy of WRGWMIB (World Registry of Groups Who Might Impact Business) and, with toe gingerly extended, test the waters:

Hmm... no new targets except the Kerala Mango Association... suppose we’re safe. But Kee-rist, must you insult everyone? ...thank god that Indian fruit outfit doesn’t subscribe...

Thus another issue would be put to bed. Such are the sensitivities of the sensitive. But I must confess, Henry always gave me plenty of rope.

Roots

Shortly after the birth of our daughter, Wimon and I came to realize that 1990s Bangkok was not a particularly nice place for a child. While the people remained as warm as ever, physically the city had become a monstrosity. Pollution soared to record levels, literally beyond measurement, and an increasing part of each day was spent idling in traffic. The city’s worst aspect was its relentless jack-hammer noise, which continued 24 hours a day.

The infamous “dog” back cover of the Gemological Digest, 1990

The infamous “dog” back cover of the Gemological Digest, 1990

Something of Myself

Following a brief stay in Vietnam, Wimon, Billie and I returned to my hometown, Boulder, Colorado. I rediscovered some of the beauties of my original home. Clean air, the change of seasons, regular exercise and, most importantly, quiet; pleasures relearned, renewed. It was in Boulder that the 1997 edition of Ruby & Sapphire was penned. Once complete, our family set off to Bangkok for publishing.

From pen to ink

All of 1996 and much of 1997 were spent giving birth in Bangkok to the new-and-improved Ruby & Sapphire. It was an opportunity to renew old acquaintances, as well as to visit gem deposits, both old and new. Rather than describe them here, I will let the reader browse our websites, Ruby-Sapphire.com & LotusGemology.com, for my writings from that period.

Westward look

In late 1997, I began working for the Los Angeles-based Gem Quality Institute (GQI), in charge of their colored stone department. Gemstone enhancement disclosure had finally become an issue of importance and GQI led the way with the most comprehensive enhancement disclosure policies in the world, one which has since been adopted by many other labs.

Dealin’

1999 found me ready for new challenges. From Los Angeles, my family and I moved down to the little town of Fallbrook, California, where I joined Bill Larson and Pala International. Pala had and has one of the finest arrays of colored stones, jewelry and minerals in the country, and Fallbrook is America’s Idar-Oberstein, home to many gem and mineral dealers and just minutes from the famous tourmaline and kunzite mines. I spent six wonderful years working with the Pala gang (and Wimon spent nine). We count the staff at Pala among our closest friends.

Bill Larson is someone who is both passionate about gems and minerals, and who does everything he can to encourage not just the same, but even greater passion in those around him. He is one of those rare individuals who is not afraid of ideas that conflict with his own.

Bill invited Wimon to organize his library and, noticing what a fine job she had done, asked her to help doing photography of gems for Palagems.com. With the assistance of other master photographers like Fred Ward (r.i.p.) and Jeff Scovil, Wimon developed into a world-class gem photographer, as you will see from her photos that grace this work throughout.

My time at Pala included several epic journeys, such as trips to Russia’s jade mines, Cambodia’s zircon and sapphire mines, Myanmar’s ruby and jade mines, and epic treks to Annapurna and Everest Base Camps in Nepal, the former accompanied by my wife, daughter and father.

Test-tubin’ again

In 2005, I was invited to join the American Gem Trade Association’s Gem Testing Center, along with one of my gemological heroes, John Koivula. We formed the Left Coast branch of the AGTA GTC and spent two glorious years working together. Not everyone gets the opportunity to work side-by-side with a living legend and I relished every minute of it. Sadly, like so much in life, it was not to last...

This period saw me traveling to Madagascar, Tajikistan, Russia’s emerald mines and the ruby, sapphire and tanzanite mines in Kenya and Tanzania, often accompanied by Dana Schorr (r.i.p.) and Vincent Pardieu.

Back to the Orient

In 2008, an ex-AGTA colleague, Loretta Castoro, invited me back to Bangkok to join a home-shopping network. For me, it was an entrée to a completely new world, particularly since so little of my life has been spent watching TV. But the world economic crisis hit just as I entered the company, and by 2010, they had gone bankrupt. In between jobs, Wimon and I ventured to Sikkim, Assam and Meghalaya in Eastern India, while Billie and I traveled through southern Madagascar with Vincent Pardieu and his merry band of field gemologists. Our travels during this period also included Vietnam, Cambodia and Mozambique.

Moving on, I ended up spending two years in Hong Kong, working for Simon Hsu’s Sino Resources, where I oversaw the production of sapphires from mines in Laos and Australia. This was a wonderful opportunity to see some of the Chinese mainland and I made a dozen trips there, including two to Tibet.

But our hearts lay in Thailand. When Wilawan Atichat of the Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand invited us to work on a new book in 2012, Wimon and I returned to Bangkok, joining our daughter, Billie, who had just graduated from UCLA. Soon Billie was studying for her FGA and joining Wimon and me traveling around the world doing research for what became Ruby & Sapphire: A Collector’s Guide, which was published in 2014. Billie and I, along with Dana Schorr, spent a month in East Africa, from Mozambique all the way to Ethiopia.

Lotus blooming

While finishing up Ruby & Sapphire: A Collector’s Guide, Wimon, Billie and I began making plans to open our own gemological laboratory in Bangkok, Lotus Gemology. This was something that had been in our minds for quite some time.

Lotus began with a simple idea—beauty is the principle source of attraction for precious stones. Thus it should also be the major focus of gemology. In other words, the GEM is the most important part of gemology.

It is our belief that gemology is not simply about counting atoms; to apply science absent a discussion of how it relates to aesthetics and desire does a disservice not just to clients, but to the jewels themselves. We do not believe that attraction can be reduced to a simple set of measurements, any more than the beauty of a rainbow or sunset can be expressed by a mathematical formula.

Rest assured, we are not Luddites. We not only appreciate science, but use it daily. At the same time, we recognize that many parts of the human experience extend into realms far beyond science. As a result, the gemology at Lotus includes not just science, but weaves into the mix history, culture, art and travel. We do this in the belief that these factors play equal roles in how humans perceive desirability and value.

Like a small French restaurant, we believe that crafting a fine meal takes time and individual care; thus our seating is limited. The translation of the intangibles of rarity and aesthetic beauty is our strength.

Lotus Gemology operates from a collective base of over eighty years of experience in the study, purchase, sale and appreciation of precious stones. Our lives have been enriched beyond measure by our involvement with these gifts of nature and we believe if we characterize them with the appropriate reverence and care, we can open this magical world to others. This is our goal.

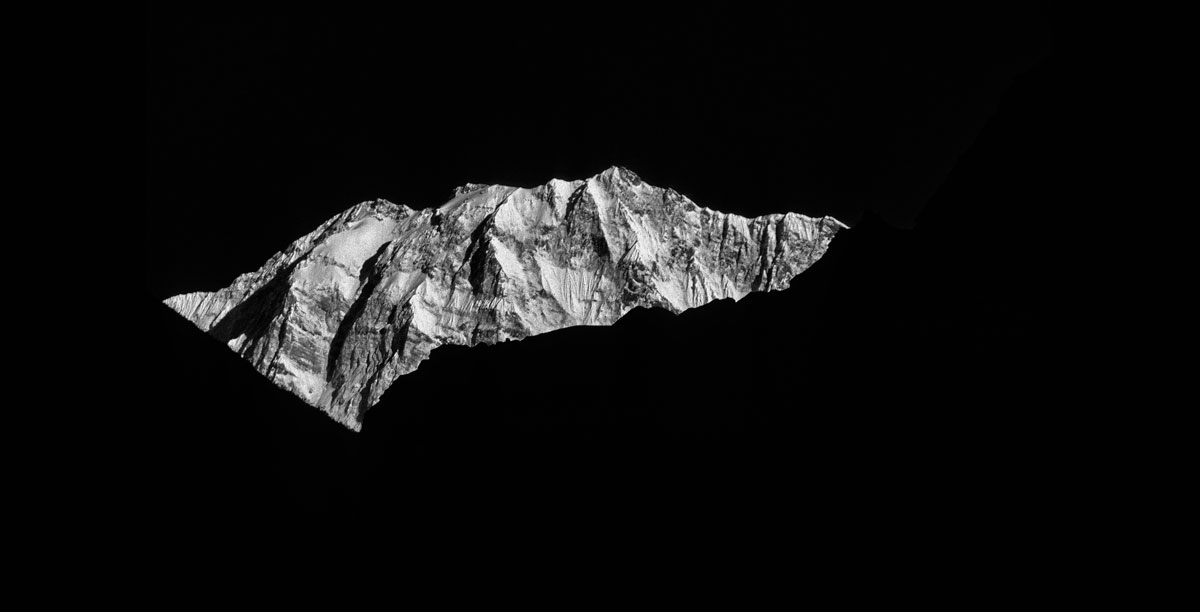

Nepal Himalaya. Photo: Richard Hughes, 2001

Nepal Himalaya. Photo: Richard Hughes, 2001

Forty years gone

It has now been four decades since my first journey to Asia, but the passage of time has done little to dull my thirst for new lands, new experiences. And while I have visited so many countries on five continents, my fascination with Asia continues apace.

Many have said about the Himalayas that memories alone are not enough. Which is why we are constantly drawn back. The first-hand experience is unlike any other. And so it has been with me and Asia. Whenever I look at a map of that great continent, I see not only where I’ve been, but where I haven’t. New adventures await. Land’s end continues to be out of sight. All it takes to get started is for someone to say: “Let’s go!” Suddenly, I’m 17 again, and university can wait. I’m all aboard for another of life’s great adventures.

Richard W. Hughes, with Wimon Manorotkul and E. Billie Hughes

Bangkok 2016