In 1996, several gemologists set off for Burma's remote jade mines, the first visit by foreigners since the early 1960's. This is the story of their epic journey.

Burmese Jade Mines • Tracing the Green Line

It is morning in Hweka, deep in northern Burma's Kachin State. Outside the window, the roar of the river below awakens us from our slumber, nudging us groggily into yet another day. Already it has been four long days since leaving Mandalay; when we will reach our destination is still uncertain. Nevertheless, we are unfazed, our spirits are high. Because we are convinced. Today is the day. Today is the day!

The road to Jade Land

Perhaps it is better to start at the beginning. We had come to these jungles to follow the green line to its source, in search of jade – what the Chinese call the "Stone of Heaven." Up until 200 years ago, jade meant nephrite, a tough, white to spinach-green stone that was the ideal canvas for China's stone carvers. Then, in northern Burma, a new type was found – jadeite. Unlike nephrite, jadeite occurred in emerald-green shades. The people of the Middle Kingdom were smitten, head over heels in love with something that came only from one remote locality in Upper Burma. It was the search for the source of this green stone that had brought us to Burma. Little did we know the trials and travails this quest would entail. This is our story, our quest for green.

Ask and ye shall receive

For over thirty years, foreigners had petitioned the Burmese government to visit the jade mines. Due to the war which had raged between the central government and secessionist rebels, the answer always came back no. But times had changed. The country was now called Myanmar. And the central government had recently made peace with the rebels. So, hat in hand, we went and asked again. And we received. They said we could go.

Traveling in Burma's restricted areas inevitably means dealing with the military, which look upon all foreigners, but particularly the press, as something to be scrutinized. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Traveling in Burma's restricted areas inevitably means dealing with the military, which look upon all foreigners, but particularly the press, as something to be scrutinized. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Don't ask, don't tell

In Myanmar, it is considered bad form to inquire about arrival times, and there are good reasons for this. The country's transportation network is, in a word, bad, operating just slightly above the stall speed of a bicycle. Couple this with some of the most rugged terrain this side of worse-to-forget-it and you get the picture. Locals understand, realizing that any answer will likely be wrong. Hence the local policy is one of pragmatism – akin to gays in the US military: don't ask, don't tell. But ask we did. And so we were told: we would leave to Hpakan on April 21. This was our first mistake, but would not be the last.

On April 19, we called Yangon, just to confirm the arrangements. And we were told: "Sorry, try again on April 28." A week later, we again called Yangon. And we were told: "Sorry, try again on May 5." So we called again on May 3. And we were told: "Sorry, the rainy season has now begun, try again later," as in November later.

Enter Stillwell's son

We had all spent enough time in Asia to realize that, while patience might be a virtue, a bit of the "I-won't-take-no-for-an-answer" impatience can also work wonders. Thus we paid a visit to Myanmar anyway, to see just how soon later could be.

|

"Vinegar Joe" Stillwell Passing through the jungles of northern Burma, it is hard enough to imagine walking, let alone fighting, but human conflict has boiled in these steaming lands for close to half a century. When the Japanese invaded Burma in 1942, the British and their confederates were left to flee to India. One man who went with them was General Joseph "Vinegar Joe" Stillwell. Over 50 years' old at the time, Stillwell would leave men decades younger in the dust as he marched. "Vinegar Joe" Stillwell was one of the finest fighting men the United States has ever produced. America's military attaché to China in the pre-war years, he was called out of retirement when the US went to war with Japan. During that conflict, he took Chiang Kai-shek's rag-tag nationalist Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) army and turned it into a first-class fighting force, routing so-called "invincible" Japanese troops all across northern Burma. But his main claim to fame was overseeing the construction of a road from Ledo, in eastern India, across to Bhamo, and then to China. The 1200km route from Ledo to Wanting, in China, cut through some of the most inhospitable jungle on the planet, spanning 10 major rivers and 155 secondary streams. So many were lost in its construction that it became known as the "mile -a-man" road. Today, due to destruction of the major bridges, only a bare track remains. But the name of its creator lives on. The trace, which passes within miles of the Mogaung-Hpakan road, is known as the "Stillwell Road."

Left to right: Chiang Kai-shek and his wife, Madame Chiang, put on a good face with Gen. Joseph Stillwell. Stillwell warned the US leadership that Chiang had little support among the rural Chinese population and that he would likely be overthrown by the Chinese communist party following the end of World War II. For his trouble, Stillwell was sacked by Washington, but his predictions later came true. The Luce family, who founded Time magazine, were evangelical Christians with ties to the Soong family, from which Madame Chiang came. They were instrumental in painting Chiang Kai-shek in a positive light, even though he was a member of a notorious triad, the Green Circles gang. What Westerners need to understand is that triads are not just a Chinese invention. It was Western governments that forced opium into China. Thus calling Chiang "corrupt" for his involvement in the opium trade while giving a pass to the various Western powers like Great Britain, Portugal, France, the US and others is the height of hypocrisy. |

A meeting was arranged, where we pressed our case. The official's concerns were real enough – this area was extremely rugged, tough enough in the dry season, let alone the wet. But we told them: "We are tough. Locals can go, so can we." Then, we brought out our trump card. Richard Hughes asked if they remembered the American World War II general, "Vinegar Joe" Stillwell (see box). Of course, came the reply. "Well," Hughes dryly intoned, "I am Stillwell's son."

When the guffaws had subsided, they agreed to give it their best shot. If it was in their power to arrange it, they would do it. As it turned out, it was not. Final approval eventually had to come from the Number 2 man in Myanmar's ruling SLORC junta. But in a week's time, we were on our way to Hpakan, center of Burma's Jade Land.

June 2: By rail from Mandalay

We begin our journey in Mandalay, a hot, dusty urban sprawl which locals say is fueled by the "three lines" – the white line (heroin), the red line (ruby) and the green line (jade). The group which assembles in Mandalay is a disparate one, consisting of a French dealer, Olivier Galibert, an American ruby and sapphire expert, Richard Hughes, a Bangkok trader, Mark Smith, and a Mogok dealer, Dr. Thet Oo. All are gemologists and all are old Asia hands, with much experience in Burma. Our guide is a Burmese army captain, a military engineer who has spent much of his career chasing rebels across the Shan hills.

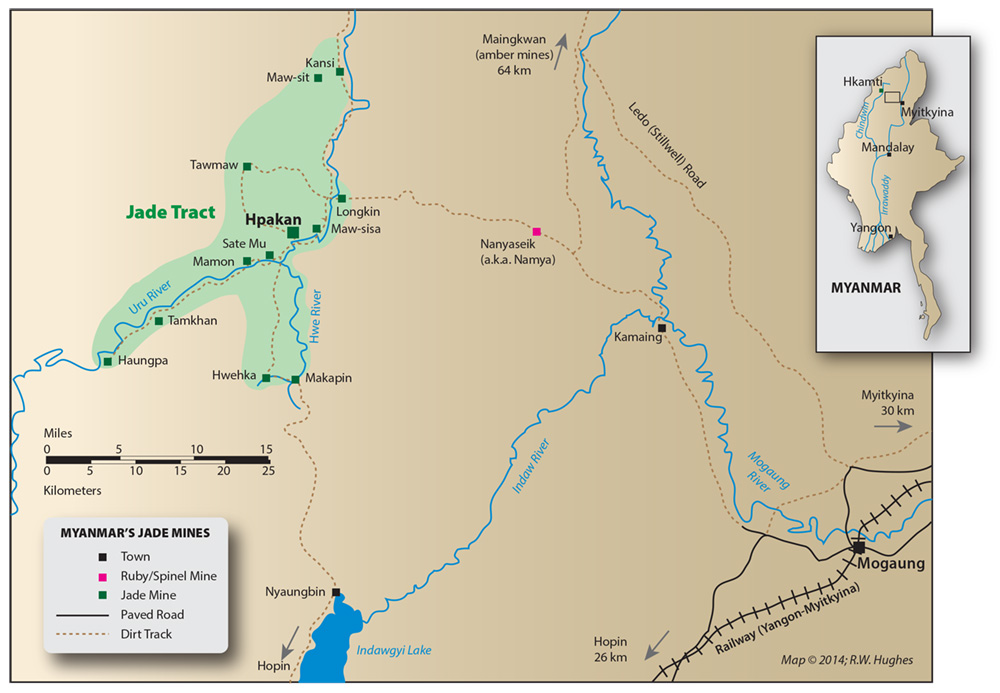

Sketch map of Upper Burma, showing the authors' route to the jade mines at Hpakan. Map: R.W. Hughes

Sketch map of Upper Burma, showing the authors' route to the jade mines at Hpakan. Map: R.W. Hughes

We board the Mandalay-Myitkyina train shortly after noon. Our first destination is to be Mogaung, the largest city near the jade mines and itself a famous cutting and trading center. From here we will proceed to Hpakan. The scheduled time to Mogaung is 20 hours, but the journey may take up to 40, due to the deplorable condition of the tracks. In 1993, the government signed a truce with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), but three years of peace have done little to wipe out thirty years of neglect. When the locomotive reaches speed, the train screeches wildly as it strains against the sides of the rails. At high speeds, our carriage rocks violently back and forth, reminding us that derailment is a very real possibility. In early 1995, at the railway bridge near Mohnyin, just such a derailment killed over 100 passengers. Thus we were not entirely unhappy with our speed.

Mosquito watch

Another aspect of the rail journey is the mice and other vermin, which scurry to and fro in the carriage. But we had little fear of them nibbling on our shoes. A pest which did scare us was far smaller – the night-biting female Anopheles mosquito – which carries deadly strains of malaria.

It was once believed this scourge could be entirely wiped out, à la smallpox, but the malaria parasite has proved a far more formidable foe. Today, the parasite has developed resistance to virtually all prophylactics. Thus the best protection is simply to avoid being bitten. Rather than quinine, chloroquine or Fansidar, we armed ourselves with insect repellent, and applied copious quantities every night of our journey.

Malaria is not to be taken lightly. The cerebral form strikes quickly and, if not treated properly, can kill as soon as 48 hours after onset of symptoms. Witness the two western reporters who ventured into rebel Burma during the late '70's. Both came down with fever upon their return to Bangkok. One immediately fled to Hong Kong, thinking the medical care in the British colony would be better. Doctors there diagnosed him as having hepatitis and 48 hours later he was dead.

Miniskirts on motorbikes

Time on the train is whiled away with the exchange of stories. Dr. Thet Oo regales us with tales he has heard of Hpakan, or "Little Hong Kong" – so-named by locals because, whatever the object of your desire, you can find it there. Among the products said to be on offer are Hennessy cognac, Rolex watches, Nike running shoes, opium, heroin, and, as Thet Oo leaned forward and conspiratorially whispered: "miniskirted girls riding motorbikes." That sure primed the pump.

The train is a' coming

At 11:00 p.m., we stop in Kawlin, a bustling market town, some eight hours and 40% of the way to Mogaung. It is near midnight, but still hot and humid. Along the platform, vendors, town criers and assorted other seers and seekers of coin shriek out the nature of their produce. The scene is a cacophony of sound and activity, as people hustle and bustle for business. Young, flower bedecked children run up and down beside the train searching for that special someone who will lighten their load. Even at such a late hour, so many are stirring – the arrival of the train provides one of the day's major events.

Little Hong Kong

Little Hong Kong

The shops of Hpakan are well stocked. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Into the night

Kawlin is but a brief respite from the monotonous pounding of the rails as we continue north into the unknown. The train moves slowly through impenetrable forest, where the dense foliage literally slaps up against one's skin. This area contains some of Southeast Asia's last remaining virgin forests, but signs of logging are everywhere. The night's full moon illuminates small towns, where shadows of hundreds upon hundreds of logs lie stacked alongside the tracks.

Occasionally, for no apparent reason, the train stops dead in its tracks, only to creep forward again after a pause of thirty minutes or so. With the onset of the monsoon, which had begun several weeks before, everything is green and the moon casts ghostlike shadows on trees stretching hundreds of feet into the sky. Wheels scream in agony as we pass through a series of low hills, with the river in the valley below. Occasionally the train nudges in and out of fog, the surrounding hills shrouded in mist. Everywhere there is jungle, green, jungle, green, ubiquitous. Humans gnaw and nibble at the forest's edges, but it continually creeps back, as relentless as the rains which give it sustenance. The train is like an intruder, its clickity clack a foreign language, tapping its message of approaching humanity like a Morse code. But if one listens closely, native tongues are heard – the buzz of cicadas, a bird's caw and the trickle of rushing water, occasionally punctuated by the howl of a wild animal from the nearby forest.

June 3: Hopin' for Hpakan

About 10:00 a.m., the train stops in the small town of Hopin, some three hours before Mogaung. Here we learn that there are two roads to Hpakan. The flatter of the two leaves from Mogaung and goes via Kamaing, while the other starts at Hopin, and heads to Hpakan through the mountains. One of the train's passengers points to some nearby trucks and declares: "There. They go Hpakan." After nearly 20 hours on the train, no further encouragement is needed. We scramble off, determined to head directly to Hpakan from Hopin.

Transport is quickly arranged, consisting of a four-wheel drive pickup, modified with three rows of seats in the bed. The cost, for what we are told is a seven-hour trip, is, frankly, astonishing – 35,000 kyat ($270 at the then exchange rate of 130 kyat to the dollar). Although we later found this to be double the local price (a 'skin tax,' as the Captain called it), we soon learned that, like the boomtowns of the old American West, the quest for green brings out that most fundamental of human characteristics – pure naked greed.

Ready for the mines

Ready for the mines

The team in Hopin. Left to right: Olivier Galibert, Richard Hughes, Mark Smith and Capt. Kin Maung Zaw. Photo: Thet Oo

Seven hours to Hpakan…

A brief meal, purchase of supplies, and then we set off for Hpakan. The dirt road heads straight for the hills, but after hearing so many horror stories about monsoon travel in this area, we are pleasantly surprised at its benign condition. Visions of cold beer in the evening, served up in imperial jade goblets by miniskirted damsels on motorbikes dance in our heads.

The first 12 km are flat; then the road ascends, twisting through the jungle up to a small military post, some 16 km from Hopin. Wreathed in several layers of sharpened bamboo and punji sticks, just one year before this base had been a lonely outpost of the Burmese army in their battle with Kachin rebels.

From the pass, the road plunges down onto the broad, flat plane that surrounds Burma's largest fresh-water body, Lake Indawgyi. In the nearby rice paddies, beautiful pink cranes are seen feeding. After two hours, we reach the small town of Nyaungbin, perched at the northern end of the lake, and halt for a brief break.

At Nyaungbin, a motorcyclist is seen removing chains. He told the authors it took him ten hours to ride from Hpakan, and he only fell five times. Photo: R.W. Hughes

At Nyaungbin, a motorcyclist is seen removing chains. He told the authors it took him ten hours to ride from Hpakan, and he only fell five times. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Nyaungbin

At Nyaungbin, we get a glimpse of the shape of things to come. The small, L-shaped town is basically a staging point, where vehicles gear up for the push into Hpakan. Our driver begins to strap on chains. "Hmm," we think, "this is starting to get interesting." Next to our truck, another vehicle is removing chains. What makes it all the more notable is that it is a motorcycle. The mud-spattered rider tells us it had taken ten hours to come down from Hpakan and he had only fallen five times. Yes, this was looking interesting, indeed.

All aboard

After a short break, we are all aboard for Hpakan. Immediately, the road changes, becoming far more rugged and muddy, while the forest creeps ever closer. This is obviously the road less traveled; whether we will be better for the experience is yet to be determined.

Due to the difficult nature of the track, we are now traveling in convoy, the lead truck with a stenciled "Bradley" on the side. As Bradley races ahead, splashing through mud, it is all we can do to keep up. Caution is quickly jettisoned as Bradley speeds over hill, dale and other obstacles. Our stomachs sicken when, at one point, he tilts onto two wheels, but, incredibly, does not tip over. Later, we learn that not everyone is so lucky. The previous day, a truck overturned near here, killing its driver.

As we crest yet another hill, a giant mud hole awaits, with a stuck truck right in our path. It is here that we see our first elephants, a ubiquitous sight in the days ahead. All along the road, the giant beasts are used to tug stranded vehicles from the mud, at a cost of 1,500 kyat ($12) per pull. But we do not yet need them, as our driver is able to squeeze by.

Mudhole #1

Mudhole #1

The first of many mudholes we encountered on the Hopin-Hpakan road. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Welcome to mudtropolis

The bottom of the next hill reveals the mother of all mud holes. Here, a ten-wheeled truck lies like a beached whale, submerged up to its windows in the slimy goo. While elephants make ready to free the vehicle, three vendors sit on the sidelines selling refreshments. The implication is clear – "You're gonna be here a while." And we will be. Andy Kaufman would have loved it.

First up is a single elephant, whose chain is strapped around the truck's bumper. When everything is secure, the signal is given. The rider gives the elephant a sharp whack on the head with his machete and all pandemonium breaks out. Trumpeting roars rock the forest's stillness as the great pachyderm strains to tug the truck free. Again and again it pulls, yanking, yanking, while the truck's engine shrieks and moans. Black clouds of diesel cloak the participants as both engine and elephant whine in agony. But all to no avail; the truck has sunk deeper still.

Andy Kaufman's paradise

Andy Kaufman's paradise

Elephants shriek and strain to pull a stranded truck from the mire of the Hopin-Hpakan road. Photo: R.W. Hughes

A second elephant is now brought to the fore, and chained to the stranded vehicle beside the first. Again, machetes flash and the jungle seethes with the sounds of the straining beasts. Again, the truck rocks and whines, but refuses to budge.

Refusing to admit defeat, Bradley decides to grasp the nettle directly. Gunning his engine, he makes a desperate dive into the hole, trying to pass alongside the truck. But it is not to be. Now two vehicles are hopelessly mired in the muck. As the sun slowly sets on this forlorn corner of the globe, its fading light carries away our hopes. And in its place, a grim realization descends – no Hpakan tonight, no miniskirts on motorbikes, no cold beer, no little Hong Kong. We now understand – we are gonna be here a while.

Ah hell, I'll walk

Ah hell, I'll walk

The rainy-season road to Jade Land is not an easy one; in many cases, it's easier to walk. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Unhappy campers

Regrouping, we discuss the possibilities. The thought of camping beside this malarial watering hole does not make any of us happy. But as the line of vehicles on either side lengthens, an idea is conjured. Why not trade vehicles? Those on the other side can take our truck and we take theirs. Thirty minutes of negotiation later, a deal is struck. We are on the road again. Our brash new driver is quickly nicknamed "Rambo."

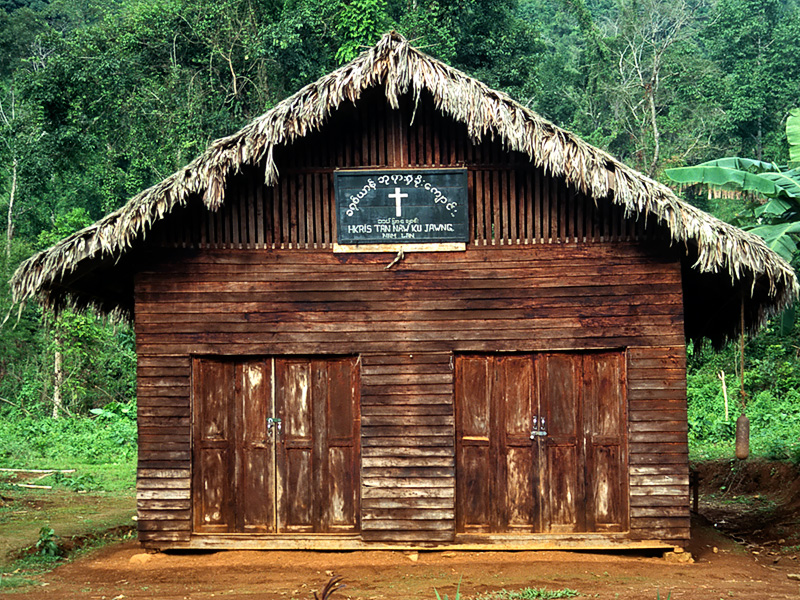

If only things were so simple. But they are not. Around the next bend, it is more of the same, mud hole after mud hole, each of which presents manifold hazards. As twilight descends, we pass small villages, each laying out the welcome mat, in the form of Tiger Beer, Heineken, Coca Cola, Pepsi, etc., for sale. We pass one house with a small white cross above the door; many Kachins are Christian – it is clear, we are now deep in the heart of Kachin land. We also pass a church, but too late – it's Monday. Still we press on.

Many Kachins are nominally Christian, but this religion is just a thin veneer on top of the traditional animist beliefs. Here is a church at Nam Lam. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Many Kachins are nominally Christian, but this religion is just a thin veneer on top of the traditional animist beliefs. Here is a church at Nam Lam. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Hogging the road

Huge trees dot the landscape as our truck variously slithers and blasts through countless mud holes. At one, where several vehicles are stranded, someone suggests we open a Pizza Hut. Now we are told we are approximately 15 miles from Hpakan, with just two or three elephant spots left to pass.

It's 6:15 p.m. and nearly dark, but we continue to push ahead. Cresting a hill, we come across a truck with a broken tie rod. No problem – except for the large pig wallowing in the mud beside it, blocking our path. Shouting and screaming produce only angry glares from the pig, which refuses to move. This is a tired statement, but one we must make – the damned swine was refusing to leave hog heaven.

Inching along

By this point, any hole under two-feet deep is a baby and hardly merits mention. But there is a problem ahead, a stuck jeep and people digging. The Willys is seriously high-centered, and no amount of our tugging and pulling can free it. So our driver decides to slip by on the edge, only to become helplessly high-centered himself. Additional vehicles halt behind us, as darkness and mosquitoes descend on the jungle.

A shovel is produced and we dig in the mire, but to no avail. Finally, a rope is procured. More than twenty of us pull and shout at the jeep, willing it to freedom from its muddy tomb. With agonizing slowness, it begins to slide forward, inches turning into feet, as we strain against the rope, up to our knees in mud. With one mighty final tug, the jeep is resurrected, amidst cheering and shouting.

Holiday in hell

Now we have only to free our truck, but this proves impossible. So, once again, rats desert a sinking ship and switch vehicles, this time to a truck loaded 15-feet high with an odd assortment of gear and people. Although Rambo tells us he will bring our gear up later, the wise amongst us grab our packs and bags. Seeing the truck's unsteady nature, Hughes and Smith decide that being in a position to leap off this tottering ship of fools beats any view of the stars from above. Thus they alight on the truck's rear bumper, where a slender space has been cleared, just enough for their feet. Again, we are moving forward on the road to Hpakan.

The truck careens wildly through the slop. Every fifty meters or so, we encounter impassible mud holes. But with a full head of steam, we slam through, only to repeat the process again and again. At times, it is all we can do to hang on, the grip made all the more treacherous due to our back packs and the fact that we cannot see the road ahead. In places, the bouncing is so great Hughes' and Smith's feet leave the bumper entirely, leaping over a foot in the air, only to come crashing back down on the bumper. During one particularly nasty portion, a Burmese man riding next to them turns and asks in perfect English: "Are you here on holiday?" Through chattering teeth, we mumble and nod, not having the heart to tell him that, if we had even a single shred of intelligence left, we would now be poolside at the Oriental in Bangkok sipping a cold drink, not clinging to some Burmese mud buggy in this god-forsaken jungle.

Bridge of sighs

After but a couple of miles, progress is halted by a bridge, surrounded by one huge mud pit. But our driver, apparently smelling the barn, decides to chance it. Gunning the engine, we speed into the gully and onto the bridge, only to have one wheel slip through the bamboo slats. Now, with the truck tottering on the brink of major disaster, Hughes decides to hell with it all. He will walk. And walk he does, like some roller-blading drunk – two paces – until his leg, too, slides through the timbers. Cursing under his breath, he gingerly extracts it and, not finding bones sticking out at crazy angles, staggers slowly into the night after the Captain, who has also decided that walking looks too good to pass up. At this point, Hughes begins to seriously question whether the green line to the source of the stone of heaven might actually be a bullet train to the hereafter. Stillwell's son is feeling mighty tired.

The missing link

At Taung Ché, our night stop, we sit down for a much deserved meal and drink… uh… barntender, make that a double. The breather gives us cause to reflect on "the road" and "the jungle." All agree that we now understand the true meaning of the phrase: "dry-season offensive." Only some beret-bedecked Special Forces yoyo would even consider fighting a war here during the rainy season. As a hubble-bubble is passed round, Dr. Thet Oo, with characteristic daring, makes a bold statement: "We can only get this kind of experience here in northern Burma." Indeed, only in this valley…

Mud wrestling

Mud wrestling

Left to right: Olivier Galibert, Mark Smith, Thet Oo and our guide, Capt. Kin Maung Zaw after arriving at Taung Ché. Photo: R.W. Hughes

While pondering that basic truth, Rambo wanders in, covered head to toe in brown ooze, but otherwise little worse for wear. Bereft of all human rodents, he dug his truck out alone and continued up the road, only to get stuck yet again. That said, he asks if driving a truck is like this in America. Sadly, we reply in the negative. One can only gain an experince like this in this valley. And we expect, some 200 millennia later, an anthropologist will dig up the fossilized remains of just such a truck in one of these mud holes and declare it to be the missing link between savage and civilization. We just hope it's not our skeletons in it.

As the night wears on, Galibert engages in a spate of arm wrestling with Rambo, while the rest of us watch, recklessly fortified by a mixture of banana leaf and something else. Rambo remarks that Galibert, with his shaved head, looks like the famous actor, Yul Brenner. And because Galibert is a happy, jolly type, he will return the following morning with his truck and take us all the way to Hpakan. On that note, we retire. Our dreams are filled with visions of cold beer in green goblets, served up by damsels in miniskirts on motorbikes.

June 4: A new day

The night had been spent in the home of a former KIA leader. As we awake in Taung Ché, the sun is shining and all well in the world. We are convinced we'll be in Hpakan by lunch. Today is the day. Today is the day!

Unfortunately, Rambo doesn't show. Thus two of us (RWH and MS) walk back down the road in search of his vehicle, the truck that will take us to Hpakan. Greeting us is a sight straight out of Dante's Mudferno. All manner of vehicles litter the road, some in the most unlikely of spots. In places, the muck is so deep it looks like only the onset of the dry season, eight months ahead, will free them from their brown tombs. It is now looking like Rambo might be a while.

The road down from Taung Ché. Photo: R.W. Hughes

The road down from Taung Ché. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Thirty minutes' walk brings us to a military post. Although we had passed it the previous night, in the confusion we had not properly checked in. Hence the sight of two Caucasians walking down the road from Hpakan sends soldiers scrambling. Expecting to be staked down in the hot sun and grilled for our secrets, instead we are offered Fantas. But there is more than a little 'splaining to do.

An hour's worth of frantic radio traffic later, our host smiles broadly and, in broken English, declares that we are "okay." But us okay folks were supposed to have left the train at Mogaung. As we are shortly to learn, an entire army unit had been sent down to Mogaung to act as our escort. Whipping out a set of US Air Force maps, ca. 1946, he proceeds to show us where we are, and where we are going. This is depressing. The previous day's and night's slipping and sliding from Nyaungbin netted us just ten miles. We are still some 25 miles from Hpakan.

But not to worry. The current unit resolves to do the dirty deed. As clouds form ominously above, a dilapidated Willy's jeep is commandeered and off we go. Just behind the jeep plods our insurance policy – a large bull elephant.

Two steps up, one step back

We push ahead. By now, clouds have turned to rain, and it surges down with vengeance. After only 200 meters, the elephant's services are called for. It is obvious walking will be quicker. Thus we all pile out and begin the trudge up the hill. As we walk, the forest echoes with the sounds of elephants trumpeting, laboring to drag vehicles up the hill.

The rain makes the clay ice-slick and it is all we can do simply to maintain balance as we skate ahead – two steps up, one step back. Rambo's no- show has created severe problems for Dr. Thet Oo and Capt. Khin Maung Zaw. Both are now reduced to daypacks and the clothes on their backs, since their main bags had been left in Rambo's truck.

Nike graveyard

The trace is a veritable shoe graveyard, muck tugging and tearing at footwear with every step. Here lies a sandal, there the sole of a boot, and over there the mud-covered carcass of what was once a pair of Nike running shoes. Halfway up the hill, the Captain's shoes give out, but he bravely strides on, bare feet sloshing through the sometimes knee-deep Kachin mud. Galibert offers the Captain sandals – which last less than half a mile before they, too, are torn to pieces.

After several hours climb, the sun greets us and we begin to head down again. But going down hill is even more difficult, due to the slippery nature of the track. All of us are thoroughly encased in the sea of brown. By 3:00 p.m., we reach the small Kachin village of Namlam. The shoes of three of our party are now destroyed, their soles literally torn off by the mud.

Captain Kin Maung Zaw's third set of footwear, just before Namlam. Photo: Olivier Galibert

Captain Kin Maung Zaw's third set of footwear, just before Namlam. Photo: Olivier Galibert

Jade!

At Namlam, a new military unit is waiting. We bid the old team farewell and, after a short rest, pile into a truck and continue the journey. The new unit is headed up by a manic major who is a dead-ringer for Charles Bronson, albeit in his Burmese reincarnation.

Slish, slosh, we splash down the track, eventually coming to Makapin (a.k.a. Makabin; 'clover tree'), roughly halfway between Nyaungbin and Hpakan. This is a substantial settlement of some 1000 people. Major Charles points at a group of men digging beside the Hweka chaung (river), and casually mentions they are digging for jade. Excitement grips us – we have finally entered Jade Country.

Our military escort radios headquarters from Namlam, deep in Burma's Kachin State. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Our military escort radios headquarters from Namlam, deep in Burma's Kachin State. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Makapin is a typical jade village, with an alluvial, jade-bearing conglomerate being worked. Although mined for decades, it has the look of a brand-new village. In the past few years, government liberalization of the mining and trading sectors has brought renewed vigor to the quest for jade. Long-abandoned mines are being reclaimed and everywhere one looks, signs of the current renaissance are on display. Makapin, with its broad array of goods, wears the new prosperity openly, shamelessly.

We stop for a drink in the riverside restaurant of the village headman, a tall, friendly Kachin. He says we are the first foreigners to visit in over thirty years and, in our honor, serves up potato chips, venison and beer, as he relates information on the village.

At Makapin a miniature Las Vegas (albeit with a wicked Macau twist) sets up every evening. Like mining towns around the world, gambling and sex are the preferred pastimes. Photos: R.W. Hughes

At Makapin a miniature Las Vegas (albeit with a wicked Macau twist) sets up every evening. Like mining towns around the world, gambling and sex are the preferred pastimes. Photos: R.W. Hughes

According to the headman, all mining here is private (meaning joint-venture). While the village is some 800 years old, only in the last four years, with government liberalization of the economy, has jade mining been revived.

It is said to cost 10,000 kyat ($77) to mine ten square feet at Makapin. With the exception of imperial green, all colors of jade are found. The most valuable piece of Makapin jade sold for a few million kyat.

All too soon, we must move on. Now our truck, packed tight with soldiers, draws a bead on the river, driving straight through the middle of the channel. Along the way, we pass steep cliffs, where the Hweka chaung has carved a narrow passage through the country rock. High on a cliff face, is a spot of bare rock. Perched like an eagle's aerie, it is a jade mine. This is but one step in the long green line, all to bring a bit of color and shine to fingers, ears, egos.

As the sun sets over the surrounding hills, we come to the important village of Hweka. This is destined to be our night stop.

Between Makapin and Hweka, the trace leads straight up the Hweka chaung. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Between Makapin and Hweka, the trace leads straight up the Hweka chaung. Photo: R.W. Hughes

One night in Hweka

Hweka is the center of jade mining in the Hweka-Makabin area. But Major Charles has other things in store for us. After a quick dip in the Hweka chaung, to kick off at least the outside layers of grime, it's back in the truck and into the night. The Major has promised us something special.

The track climbs steeply above town as we lurch through the mud, heading towards the jade workings near Kadonyat. Nearing the top of the hill, the inevitable occurs – stuck again. But no worry. Amidst vigorous pulling and shouting, the vehicle pops like a cork out of the mud, landing at the doorstep of something special – the local disco.

True, there is no mirrored ball, but the one-room hut has that special something – atmosphere. We soak it up by the bottleful. Eyeless in Gaza? No! We are shoeless and muddy in Hweka and dance the night away. Once again, Dr. Thet Oo soberly reminds us: "We can't get this kind of experience anywhere else." Verily.

June 5: Hpakan or bust

As we awake in Hweka the next morning, the tension is palpable. A peek out the window reveals the expected – gray and green – gray skies, green jungle – our constant companions. When we began this journey, our thoughts were filled with how much time we might spend at Hpakan, whether or not could visit the famous deposits of Tawmaw and Maw Sit Sit, etc. Now we are concerned with only one thing – actually setting foot in Hpakan. Little Hong Kong is so close we can smell it, taste it, tease its rough texture with our tongues.

Many Kachins are animists, people who worship the nats (spirits) said to reside in hills, trees, lakes and other natural features. While Burmese settlers have brought their Buddhist beliefs and European missionaries introduced Christianity, to many people in these hills, it is but a thin veneer. Scratch the surface and one finds the old beliefs, which still remain strong. Perhaps for good reason, as the previous night's events suggested.

The small village of Hweka, with the rain-soaked track to Hpakan leading into the mist. Photo: R.W. Hughes

The small village of Hweka, with the rain-soaked track to Hpakan leading into the mist. Photo: R.W. Hughes

The night before, we were told we could make it to Hpakan the next day, so long as it didn't rain. And it didn't, for rain is not a proper term for what poured down that night. No, this wasn't rain, this was a torrent, a rage, a hurricane blast of fury unleashed by some power greater than any of us had previously known.

Shaken, we climb out of bed and into the new day. The first order of business is to resupply. All of us are in need of fresh footwear, among other things. But in Jade Land, the markets are well stocked. First we slip into brand spanking new Chinese Super Dog™ socks. Then come the camouflaged canvas jungle boots – a wicked crossbreed of Converse All-Stars and Rambo running shoes. Slapping Moon Rabbit™ batteries into our torches, we are locked, loaded and primed for whatever the Burmese jungle might care to dish out. Bring it on, baby. Today is the day!

The trace leads straight up the mountain face on the north bank of the Hweka chaung. But the previous night's downpour has made it impossible for our truck. At this moment, fortune smiles upon us, in the form of a caterpillar-treaded backhoe owned by a jade miner. Like a giant insect, the great mechanical beast lumbers over to where our truck is resting and, with agonizing slowness, raises its arm high into the sky. Then, with a deft move, the bucket empties its contents. On the mud in front of us is a slender thread – a steel cable that will hopefully haul us into heaven.

Hooked up

Ever-so-slowly, the spider pulls us up the mountain. So slick is the trace that even the caterpillar's treads spin and whirl in the mud. Now understanding the drill, yet again, we set off on foot.

Signs of jade-mining lie everywhere as we continue towards and past Hpaokang, about one mile from Hweka. At the top of the mountain, ingenious mining pools have been excavated. When enough water accumulates, a gate is opened, allowing water to rush down and "sluice" the hillside below. Later, men will come to examine the boulders thus uncovered, looking for that special texture and feeling that sends the pulse racing – jade.

Utilizing its mechanical arm, a backhoe drags our truck out of Hweka. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Utilizing its mechanical arm, a backhoe drags our truck out of Hweka. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Back to the soil

Walking along the ridge here, where the sun has now come out, is one of the most pleasant stretches of the journey. We pass donkey trains and small villages, along with the ubiquitous vendors selling refreshments. The forest, in its stillness, is lovely, green-green, like the stone which brought us here. But as quickly as the jungle seduces, it also reminds one of its force, its power.

Rounding a bend, we see a woman sitting on a blanket, washing tomatoes. Coming closer, we see why. A truck identical to ours lies in the gulch below, cocked at an obscene angle. Scowling, she explains to us that, when the mud bus did its impromptu disappearing act into the ravine below, she was on it. And she is none too pleased – all her tomatoes got soaked.

One victim of the road into Jade Land. Photo: R.W. Hughes

One victim of the road into Jade Land. Photo: R.W. Hughes

While watching an elephant attempting to extract the wounded truck, we hear the approach of another vehicle. Could it be? Yes, it is. Our ride is with us again. The road now wriggles and winds over the Kachin countryside like a long brown snake. The previous night's rain has made the track all the more treacherous, particularly when moving down hill. So steep is it that, at times, we slide sideways with a sickening motion, and it appears we will overturn. Our driver wrestles with the wheel as we continue the plunge downward, only to right the vehicle and repeat the process around the next corner.

As we lurch over hill and dale, the crest of one rise reveals a sight forever etched in our memories. Seven hours had turned into several days. But, there, below us, is a lush valley. And in that valley lies a town. Hpakan is at our feet.

Valley of Jade

Valley of Jade

The towns of Sate Mu (Sine Naung) and Hpakan, seen from the Hweka-Hpakan road. Photo: R.W. Hughes

June 5 – Hpakan

For over thirty years, Burma's military government has kept the Crown Jewel of Jadedom locked away like a virgin in a tower. It has taken four long days of travel, with the past three yielding a scant 35 miles, just to get a glimpse of the tower. But here we stand, on the cusp of Hpakan. Rapunzel has let down her long hair – now we are poised to ride the strand into a fairy-tale world, one where dreams come true and all the dragons are colored imperial green.

Little Hong Kong – Town at the end of the universe

Considering the difficulty in getting here, what awaits us in the valley below is all the more amazing. Amongst locals, Hpakan is known as "Little Hong Kong" because, like the British Crown Colony, you can get anything you want. Whatever the apple of your sweetheart's desire, it's available in Hpakan. Just be prepared to pay the price, which, is two to three times that found elsewhere in Burma. But exorbitant prices matter little at Hpakan, a topsy-turvy town in a topsy-turvy country, where today's taxi driver just might be tomorrow's tycoon.

The wild, wild east

Driving into the Uru (Uyu) river valley, we first come to the town of Sate Mu (previously called Sine Naung), which is actually bigger than Hpakan itself. Picture Cripple Creek, Virginia City, Fairbanks and every other wild-west town in its heyday and you have some idea of this place. Driving down its dusty boulevard, one almost expects to hear a honky-tonk piano, or see somebody come flying through a saloon window. We are immediately struck by its temporary air – many dwellings are little more than makeshift shacks and almost everything is of recent construction.

Passing along the bustling main street we see signs for Rolex watches and Hennessy cognac, testifying to the tremendous wealth simmering just beneath the dull exterior. Above the tin roofs are satellite dishes; beyond that lie the green hills, splattered everywhere with the brown of mining activity. In places, entire mountaintops are eaten away, as the human quest for the green stone oozes deeper and deeper into the surrounding jungle.

We continue on to Hpakan, which lies astride the Uru River. After a brief stop at the Government guesthouse, to wash up and check in with the local police, we plunge straight into this green chasm that is jade.

|

Jade – Stone of heaven In humanity's entire recorded history, there has never existed a more intimate relationship between a people and a stone than that between the Chinese and jade. To the people of the Middle Kingdom, jade was not simply hardened earth – but, instead, crystallized magic – a tiny piece of heaven bequeathed by the gods to those of us destined to suffer here on earth. It was literally the link between heaven and earth, the bridge that allowed mortals to cross over into immortality. For people of the Middle Kingdom, the green stone was valued beyond all else. Gold and precious stones might capture interest in the rest of the world, but, in China, they were simply also-rans. In Chinese athletic competitions, ivory was given for third place and gold for second. Jade was reserved solely for the winners, including high officials in the imperial court, because, as the saying went: "Gold has a price – but jade is priceless." Within jade's verdant interior, the Chinese saw all that is good with humanity – virtue, purity, justice, humanity, and more. But while jade itself might be priceless, many are willing to extract coin for the honor of holding it in one's hand, or wearing the green stone on a finger or ear. In fact, the search itself has its price. So what exactly is jade? In the Orient, just about anything translucent and green has been called jade at one time or another. But the Occidental psyche, with its propensity to pigeon-hole, does not sit well with such indifference to definition. Just how does one classify a piece of heaven? If you are Chinese, you don't even bother trying, which was why it was left for the intruders from the West to finally cross all the t's and dot the i's of this most arcane of gem substances. In 1863, a French mineralogist, Alexis Damour, analyzed the bright green stones from Burma. Finding them different from ordinary Chinese jade (nephrite), he named the "new" jade, jadeite. Today, gemologists apply the term jade only to nephrite and jadeite. Nephrite is a fibrous subspecies of the actinolite – tremolite series, while jadeite is a member of the pyroxene mineral group. The ideal composition of jadeite is [NaAl(SiO3)2], but it is frequently mixed with diopside [CaMg(SiO3)2] or acmite [NaFe(SiO3)2]. Pyroxenes rich in both the jadeite and augite endmembers are known as omphacite. Jadeite rich in iron (mixed with acmite) is a dark green to black color and is termed chloromelanite. Some boulders display this black, chloromelanite skin, which, according to Burmese miners, is bad, "infecting" the stone, and a harbinger of bad luck. |

Building the pyramids

Building the pyramids

Hpakangyi, where in 1997 over 10,000 people were building a bridge to heaven. Photo: R.W. Hughes

June 5–7 – Hpakan

Greenhorns in Greenland

Upon reaching the mines, the first question any self-respecting gemologist asks is: "By jove and George, how in the heck do they do it?" Meaning, how do miners separate the quite occasional jade boulder from the thousands of others which they also dig up and which look so completely similar that, if you or I had found it, we would simply chuck this potential fortune straight into the neighbor's back yard? This is the question.

Our investigations did put the question to rest, somewhat. Repeated questioning of various and sundry jade traders, cutters and miners yielded up the following pearls of wisdom:

Identifying jade

To separate jade from ordinary boulders, miners look for something which, in the vernacular is called yumm, a fibrous texture. Ordinary boulders show a reflection of mica or sand, while jadeite is smooth, with yumm, and without particle reflections.

In addition to the fibrous texture, jadeite also tends to stick slightly to one's hand or foot under water. It also has a different sound when struck with a pick, as well as having a greater heft (density) than ordinary stones.

Miners also look also something called shin, which, from what we could gather, is the type of sheen seen on schist. Black shin is said to "damage" the stone, apparently being an indication of increased iron content (chloromelanite). They also look for the show points, where the jade color shows through the skin.

Rough and cut heaven. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Rough and cut heaven. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Jadeite types

Jade is roughly separated according to the manner in which it is mined. By far the vast majority is recovered from alluvial deposits of the Uru River conglomerate. This occurs as rounded boulders with a thick skin and is termed river jade. In contrast, mountain jade appears as irregular chunks with a thin skin, and is recovered directly from in situ deposits. The green and lavender colors are independent of the deposit type, but red to orange jade is limited to those pieces of jade recovered from an iron-rich soil. The reddish color results from a natural staining of the porous jade's skin.

The Hutton-Mdivani jadeite necklace is one of the most famous pieces of jade jewelry in the world. It was purchased at auction in April 2014 by the Cartier Collection for a stunning US$27.44 million, a jade auction record. The necklace features 27 superbly matched jadeite beads ranging from 15.4 to 19.2 mm. Myanmar is the only country in the world that produces jadeite of this quality. Photo: © Sotheby's

The Hutton-Mdivani jadeite necklace is one of the most famous pieces of jade jewelry in the world. It was purchased at auction in April 2014 by the Cartier Collection for a stunning US$27.44 million, a jade auction record. The necklace features 27 superbly matched jadeite beads ranging from 15.4 to 19.2 mm. Myanmar is the only country in the world that produces jadeite of this quality. Photo: © Sotheby's

The business of jade

From the time jade is won in the Jade Mines area until it leaves Mogaung in the rough for cutting there is much that is underhand, tortuous and complicated, and much unprofitable antagonism. In my opinion the whole business requires cleansing, straightening and the light of day thrown on it. Major F.L. Roberts, formerly Deputy Commissioner, Myitkyina

It is said that the jade business involves "luck." That's like calling a lottery ticket an investment in the future. The jade business is not about luck, it's about strapping your hopes and dreams straight onto the rim of the roulette wheel and letting the creator give it a long, hard spin. Just how much joss is involved is illustrated by the tale of U Tin Ngwe, one of Hpakan's many lao pan (kingpins). He got his start behind the wheel of a large piece of rolling Japanese steel with a "taxi" sign on top. One day, a local jade trader he picked up offered him a spin of the green wheel, in the form of a grab bag of jade boulders. Picking up each piece, he studied them carefully. "Why not," he thought, as he forked over 3,000 kyat ($23) for the heaviest boulder in the lot, "I feel lucky." He felt even luckier after selling the piece to another trader for 650,000 kyat ($5000). And that trader felt even luckier still after selling the exact same piece for over 3,000,000 kyat ($23,076). "Hmm," he thought to himself, "this jade stuff is interesting." It was so interesting that, today, U Tin Ngwe owns several mines and is one of the biggest traders in the valley. When the steel ball finally came to rest, it had stopped at his number.

A room with a view U Tin Ngwe, who went from taxi driver to jade kingpin almost overnight, stands atop a small fortune of jade at his Hpakan home. Photo: Olivier Galibert

A room with a view U Tin Ngwe, who went from taxi driver to jade kingpin almost overnight, stands atop a small fortune of jade at his Hpakan home. Photo: Olivier Galibert

|

Be all you can be For Burma's military, the jade mines represent a big fat pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. And a stint at the mines is the payoff for a job well done. The rewards for being stationed there are many, for, in a district where coin flows like water, those positioned directly at the well get to drink to their hearts' content. During our time in the jade mines district, we came in contact with countless military officers, but did not meet a single one who had spent more than six months in the area. You see, when it comes to jade, others must also get their chance to drink. |

Shooting craps

Of course, every crapshoot has its losers, as well as winners. None who lived in Bangkok in the late-1970's can forget the story of… let's call him Sia Poh, who had invested a small fortune in one promising jade boulder. Many others were also eager to possess it; one went so far as to offer him several times his money. But Sia Poh refused to sell. He would cut it himself and, in the process, squeeze every possible drop of profit from the green stone. Alas, it was not to be. Cutting open the stone revealed but a cheap, ornamental-grade lump, worth perhaps $50. Lady luck had passed him by. In Sia Poh's case, the steel ball eventually stopped right between his eyes – from the muzzle of the weapon with which he blew his brains out.

Judging quality – smoke and mirrors

Much of the mystery about the jade trade concerns just how a trader judges the quality of something encased in a rust-like oxidation skin so dense it hides all traces of color within.

Traders will often wet the surface of a boulder to better see the color lurking underneath. They also utilize small metal plates and penlights. The plate is placed on the surface at a likely spot and a penlight shone through from the side furthest from the eye. This reveals color in the absence of glare from the light.

According to traders and miners to whom we spoke, one looks for something they call pyat kyet (literally 'show points'), which are areas where the skin is thin enough to see through. And if there are no such show points? Heh, heh, heh. If we could answer that one we wouldn't be telling you now, would we?

Traders use penlights and small metal plates to examine rough jade in order to try and decipher what lies within. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Traders use penlights and small metal plates to examine rough jade in order to try and decipher what lies within. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Down at the saw mill

In an effort to get right down to brass tacks, much jade is simply sawn open; this is the approach used at the government-sponsored auctions in Yangon. But as owners don't particularly like their boulders defaced in such a manner, one has to pay to play that game. Parting a boulder down the middle has the added danger that one may cut right through a good area.

Desperately seeking green

Experienced jade traders are said to be able to predict, by studying the outside of the boulder, what the inner color will be, but anyone who has ever seen boulders sawn open can prove the lie in that old wives' tale. Even for experts, much guesswork is still involved. Before cutting, traders look for color spots at the show points. Color spots going all across a stone infer that color is relatively consistent across the piece.

Before cutting, the surface is carefully examined to select the best place for sawing. While it is difficult to see through the skin, some cracks can be seen. This is important, as fractures can have a dramatic impact on value. There is no specific formula for cutting – it all depends on individual judgment and the rough's features. In buying, say, a five-piece lot, sometimes all are good, and sometimes all are bad. Much depends on luck, or, as the great 11th-century gemologist, al-Biruni, put it: "God grants honor to some and disgrace to others."

Opium and the jade trade

According to one Bangkok source, mining concessions in the Hpakan area are granted according to the projected value of the jade in the ground. Of course, the best spots cost lots of money, which the (mostly) Chinese mine owners pay to the central government. According to this source, only those with mighty deep pockets get involved and, in these hills, that usually means opium merchants.

This source, who is quite close to one of Burma's top jade traders, told us that the jade business is often simply a sideline. Those in the drug business don't mind putting up a billion kyat (about $7.7 million) and only getting half back, because that half is now "clean" money. They can also afford to stockpile jade, giving buyers the impression that fine stones are more rare than is actually the case.

Those in the drug business also have a ready means to control the miners, many of whom are opium or heroin addicts. Diggers believe that taking the drug will help prevent malaria and other diseases, but it's more likely the drug just eases the pain which digging holes in the ground inevitably brings. In any event, once addicted, the bosses can then easily control their workers, by regulating the supply of the drug.

The cocktail of opium and jade is a highly inflammable one and mafia-type gangland violence occasionally erupts. Just a few weeks before our visit, a major miner (and also, reputedly, a drug dealer) was murdered in Myitkyina. The official version of the killing was that it was the work of a "mad man."

Upon signing the peace agreement, soldiers from the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) were legally allowed into Hpakan for the first time. They didn't like what they saw. Heroin was being openly sold, almost like Coca Cola on the street. But they solved that problem. Rounding up close to 80 heroin dealers, they took them down to the river, put a bullet in the backs of their heads and dumped the bodies into the Uru chaung (river). Heroin is no longer sold openly in Hpakan.

Taxing questions

In all good businesses, it is inevitable that the government should want a piece of the action, and so it is with the green stone. Each jade boulder we saw had writing on it. This is a registration number, along with the weight, signifying that tax has been paid on the boulder. Tax is paid in Hpakan, after evaluation by a government-appointed committee. The levy is 10% of the appraised value, but since many who sit on the committee are traders themselves, valuations tend to be "generous."

Without paying tax, it is theoretically illegal to cut a boulder. But it does not take too great a leap of faith to see people simply cutting boulders without paying tax. In any event, today, almost all the boulders are said to be "legal," meaning that tax has been paid.

The danger of mining jade is ever-present, as these benches behind Sate Mu so clearly illustrate. Photo: R.W. Hughes

The danger of mining jade is ever-present, as these benches behind Sate Mu so clearly illustrate. Photo: R.W. Hughes

A mining we will go

In Hpakan, we hire a car to take us to Lonkin, several miles away. Along the way, we stop at Maw-sisa, among the most active and interesting jade mines in the Hpakan region.

Maw-sisa is, in many respects, the quintessential mine, with jade recovered from alluvial deposits in the Uru river conglomerate. This formation is as much as 1000-feet deep in places, and present mining has just scratched the surface. Thus jadeite hoarders should take note – from what we could see, there is a good millennia or three's worth of material remaining to be extracted.

Each mining claim is just 15-feet wide; to keep from encroaching into the neighbor's area, a thin wall of earth and boulders is left as a partition. When seen from above, the result is spectacular – several square miles of stair-step like benches, resembling nothing so much as a massive archeological dig. But diggers here do not search for mere bones or shards of pottery. Instead, they seek the Chinese Holy Grail, small pieces of heaven.

The landscape outside Sate Mu is scarred from decades of jade mining. Photo: R.W. Hughes

The landscape outside Sate Mu is scarred from decades of jade mining. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Dig it

At Maw-sisa, diggers were mining a black layer, locally termed ah may jaw. While jade is said to be richest in this layer, it can occur anywhere in the conglomerate. The first step in mining is removal of the overburden, taung moo kyen (literally 'head cap removal'). Since the overburden is also conglomerate, it may also contain jade, so the workers must search this, too. We saw people working about 50 feet into the conglomerate, which is stripped away with primitive tools.

Miners were asked how often they find jade. They said it depends on luck. While some days they might find up to 25 pieces, other times they might go for days without finding anything. In terms of size, some boulders are 200–300kg, some even as big as a house, but most are less than 1kg.

Mining jade at Maw-sisa, near Lonkin, Burma. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Mining jade at Maw-sisa, near Lonkin, Burma. Photo: R.W. Hughes

At one spot, we saw two people carefully washing a blackish boulder, apparently to see if it was jade. When approached, they quickly tossed it aside, but then went back to it after we left. From a distance we watched. Brows furrowed as they scraped away at it, only to throw it away in the end. Apparently even the miners themselves sometimes have difficulty in identifying the look of heaven.

Walking back through the village, we saw some people smoking opium, while others were busy downing the local whisky. A few meters away there was a sign in Burmese giving some local laws:

- Do not smoke while walking (to prevent fires, which are common in the area).

- Do not consume alcohol or drugs.

- Respect other cultures (people of a variety of ethnic groups live in the area).

Well, two out of three isn't bad.

Bug spray

Bug spray

Malaria is a major concern for anyone living or traveling in the jade-mines area. In this land of animism, the preferred local solution is embossing the skin by pinching it with a coin. The Maw-sisa miner at left is prepared for any kind of flying pest, as was Richard Hughes after he had the treatment applied. The efficacy of this bug protection was made crystal clear in Mogaung, where Hughes and Galibert slept side-by-side in the same bed. Come morning, Galibert's body was covered with bedbug bites, while Hughes was untouched. Photos: R.W. Hughes (top) and Mark Smith (bottom)

Dike mining

It is said that to find a dike is to become an instant millionaire. For whilst ordinary miners flail away in the common soil, only rarely turning up a boulder of jade, the dike is the mother lode itself, a bridge straight to heaven.

In the Hpakan area, several primary outcrops of jadeite have been located, the most famous of which is at Tawmaw. Formerly, miners employed fire and water to break away pieces of the jade. Today, peace has another dividend – dynamite – a godsend when dealing with a rock so tough that a day's worth of drilling might only penetrate 12 inches.

Unfortunately, the road to Tawmaw in the rainy season is… iffy. After an hour's worth of radio traffic at the Lonkin military base, we were told that only the first few kilometers were passable. Thus we set off for the mining site of Masamaw, on the way passing through a small village called Kademaw. Later, we visited a mine operated by the NDA, one of the Kachin resistance groups.

Slowly down the river

For over 200 years, man has scoured the banks of the Uru River in search of jade. The keepers are quickly put away, with the others simply discarded, giving the area the look of one large anthill. Centuries of labor have piled the banks high.

Jade is not the only treasure yielded up by the river. Much gold mining is also in evidence, with the miners utilizing small, portable sluices featuring ingenious bamboo riffles.

Near Sate Mu, finding jade is sometimes as simple as a walk along the banks of the Uru River. Of course, you might have to examine an awful lot of rocks in the process. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Near Sate Mu, finding jade is sometimes as simple as a walk along the banks of the Uru River. Of course, you might have to examine an awful lot of rocks in the process. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Submarine mining

During seasons when the river is high, particularly at Mamon, men dive for jade. Air is supplied via a crude air pump, something akin to a triple bicycle hand pump. While those on land furiously works the pump, the diver hops into the water and searches for jade with the plastic hose between his teeth, all the while hoping and praying those up above don't forget just who's down there.

Friday, June 7, 1996: The road to Mandalay

Until recently, the only way that Hpakan could be supplied was by convoy from Mogaung – fifty or more trucks – along with a healthy dollop of Burmese military might. Fighting between the Burmese army and the KIA is now over, but the struggle continues, this time against nature.

To leave the jade mines, we would take this Hpakan-Mogaung road, the "good road," as we were told. Unfortunately, this turned out to be every bit as wretched as the one on which we had come up, only flatter and busier. Just outside of Lonkin, it degrades into a sea of mud, with all manner of stranded vehicles. Coming upon one stuck lorry, which was hooked up to a rather ingenious winch, we asked how long he had been stuck. The answer surprised even us. He had been resting in the same mud hole for ten days.

|

Nanyazeik ruby mines Jade is not the only gem found in these hills. The famous Burmese amber deposits are located in the Hukawng Valley, some 60 miles north of Hpakan, while ruby and spinel are had at Nanyazeik, a few miles from Kamaing, on the Mogaung-Hpakan road. We inquired about ruby as we stopped at Nanyazeik (locally termed 'Nanya' or 'Namya') during our June 1996 visit and were told that there was mining, but it had yet to receive official sanction. One Burmese source told the authors that he had seen some ruby from Nanya, and it was good, similar in features to that from Mogok. In Mogaung, we purchased one 0.5 kg rounded piece of low-grade ruby, which was offered as red jade. This was possibly from Nanya. [Note: Richard Hughes visited Nanyazeik a second time in March 1997 and again inquired about ruby mining. He was told the deposit was being worked a bit. This began to change in the year 2000, with a mining rush. Nanyazeik produces pink to magenta colored rubies and star rubies of fine quality, along with hot pink spinels] |

Jumbo journey

Our journey from Hpakan to Mogaung was as follows: truck, jeep, foot, elephant and truck. Most interesting was the elephant. Two beasts were initially offered, but since one was already on his third "driver," having killed the previous two, it was clear which one to take. As the jumbo knelt down, we climbed aboard.

Comfort is not one of the pluses of elephant travel, but we can say this – it absolutely does not get stuck. The driver told us he had purchased the beast many years before for 60,000 kyat ($462), and had recently turned down an offer of three million ($23,076). He also told us the elephant's age: "She's now 21" he said and, with a wink, "still a virgin."

The final leg of the journey was completed by truck. It had one of those fancy do-hickies on the dash, the kind meant to tell you when you are leaning, and when you are leaning too much. In our case, it always seemed to be the latter, but the gauge must have been broken, because even when the little yellow needle had tilted several degrees beyond the scale, we still didn't tip over.

We will not go into the many trials of the rest of the journey. Suffice to say that, in the end, the Burmese jungle spit us out, panting and dusty, at the Mogaung trailhead, over 12 hours after leaving Hpakan. Our night was spent at Mogaung's Dollar Lodge, which cost three.

Until recently, the only way Hpakan could be supplied was by convoy-fifty or more trucks-along with a large helping of Burmese military might. Although fighting between the Burmese army and the KIA is now over, the struggle continues. But today, the enemy is nature, as this photo of the "good" road between Mogaung and Hpakan shows. Some trucks along this road had been stuck in the same spot for ten days. So high is the demand for transport to Hpakan that the owner of this truck made back the truck's purchase price within six months. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Until recently, the only way Hpakan could be supplied was by convoy-fifty or more trucks-along with a large helping of Burmese military might. Although fighting between the Burmese army and the KIA is now over, the struggle continues. But today, the enemy is nature, as this photo of the "good" road between Mogaung and Hpakan shows. Some trucks along this road had been stuck in the same spot for ten days. So high is the demand for transport to Hpakan that the owner of this truck made back the truck's purchase price within six months. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Saturday, June 8, 1996: Mogaung

Considering the large quantity of jade mined in the Hpakan area and the tremendous difficulties involved in its transportation, it is surprising that so little seems to be cut on site. But this is the case. Other than one market just outside Lonkin, we saw no cutting in the Hpakan area. Instead, most jade is hauled out for cutting elsewhere.

Mandalay is by far the biggest cutting and trading center for jade in Burma, but there is also a jade market in Mogaung. The morning we visited, some 200 people were involved in cutting and trading jade. In addition to jadeite, the unusual ornamental gem material, maw sit sit, was also on offer. One member of our party (TO) bought a boulder of maw sit sit which weighed over 30kg.

Bamboozled

Bamboozled

Final polishing for jade cabochons is often done with a piece of bamboo mounted on the end of a lathe. This photo was taken in Mogaung's jade market. Photo: R.W. Hughes

End of the green line

A hill just above Sate Mu looks down upon one of the most remote and inaccessible mining localities on the face of the earth. On this hill stands a 30-foot cross, symbol of the Kachins' predominantly Christian faith. But this is no ordinary crucifix. The color of Jade Land is green and the color of this cross is also green – green like the jungle on the surround hills – green like the stone which has brought us here – green from the hundreds of jade plates that coat its surface.

In the valley below, ant-like figures labor in the river, searching, seeking, hoping to find that one special stone, that green rock which will bring them a slice of heaven right here on earth.

Some might see this search and, indeed, this cross, as a tower of babel, a symbol of man's vain quest for material wealth. But it matters not to those who search for the green stone. The fact is that the green stone exists – no preacher or holy book, be it Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, Tao or Christian, can change that.

Is the green stone, as the Chinese assert, a bridge to heaven? Although we have traced the green line to its terminus, all the way to its very apex, we are still unable to provide an answer. But one thing is certain: as long as the demand for jade persists, man will continue to follow the green line. And that line will continue to lead straight to Hpakan.

The famous jade cross above Sate Mu, near Hpakan, Burma. Photo: R.W. Hughes

The famous jade cross above Sate Mu, near Hpakan, Burma. Photo: R.W. Hughes

About the authors

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.

Olivier Galibert, a Hong Kong-based gem dealer, specializes in fine precious stones and pearls. He spends over half the year traveling throughout Asia in search of the rare and beautiful.

American Mark Smith has resided in Bangkok since the early 1980's, where he operates one of the Thai capital's finest colored stone wholesale houses.

Dr. Thet Oo (R.I.P.) of Rangoon and Mogok, Burma, was a second-generation trader in precious stones, specializing in star rubies and sapphires.

Author's Afterword

This article resulted from a June 1996 trip to Burma's jade mines, the first visit by Western gemologists in over 30 years. My pale attempt at describing the indescribable was published in Jewelers' Circular-Keystone in two parts (1996–97; Vol. 167, No. 11, November, pp. 60–65; Vol. 168, No. 1, January, pp. 160–166).

In March 1997, Fred Ward and I made a second trip, accompanying a German film crew. Although we were able to spend more time at the mines, the Burmese military intelligence (MI) officials who accompanied us made it a royal pain in the ass. I was the only one in the group who had a clue about the area (other than a lao pan's mine manager who accompanied us), so the MI men naturally assumed I must be an American spy. Ha! Little did they know that I am just about the last person the US government would select for such a task (in line right next to Fidel Castro). In any event, it was the first time I had been arrested without committing a crime (a common occurrence in Burma for locals, I am told) and by the end of the trip Fred turned to me and said: "In the immortal words of the Hollywood starlet: 'Who do we have to screw to get off of this film.'" The second trip is described in another article, Heaven and Hell.

Much later, in September 2004, Dana Schorr, Detlef Dirksen and I made yet another rainy season trip to Hpakan. What we found at that time was the earliest signs of times to come. Most mines had become mechanized. Oh, how quickly things can change. As I write these words in April 2014, Myanmar's jade mines are on the brink of extinction, due to the intensity of modern mining technology brought to bear on what was once such a remote, poorly developed place.

See also:

- Burma's Jade Mines: An Annotated Occidental History

- Heaven and Hell: The Quest for Jade in Upper Burma

- Burmese Jade: The Inscrutable Gem

- Jade Buying Guide • LotusGemology.com

- The Chinese Box • A Guangzhou Jade Market Puzzle

- From Russia With Jade

.jpg)